Botanicals In Blue: A Victorian Woman’s Take On Algae

Anna Atkins, the first person to publish a book of photography, showed a predilection for botany.

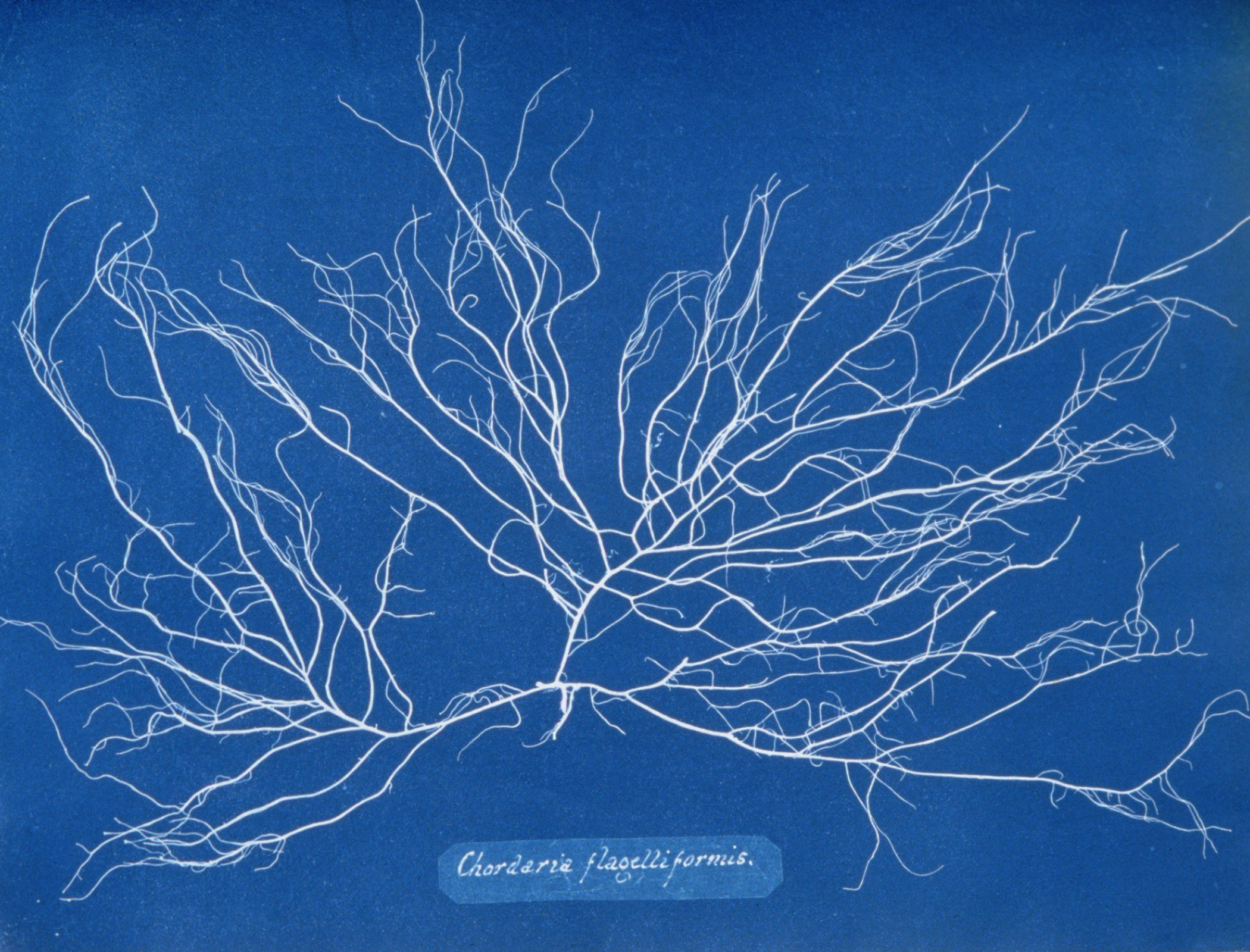

Chordaria flagelliformis, from "British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions," by Anna Atkins (March 16, 1799–June 9, 1871). The images in this article were digitized from Sir John Herschel's copy of the book. Image courtesy of the Spencer Collection/The New York Public Library

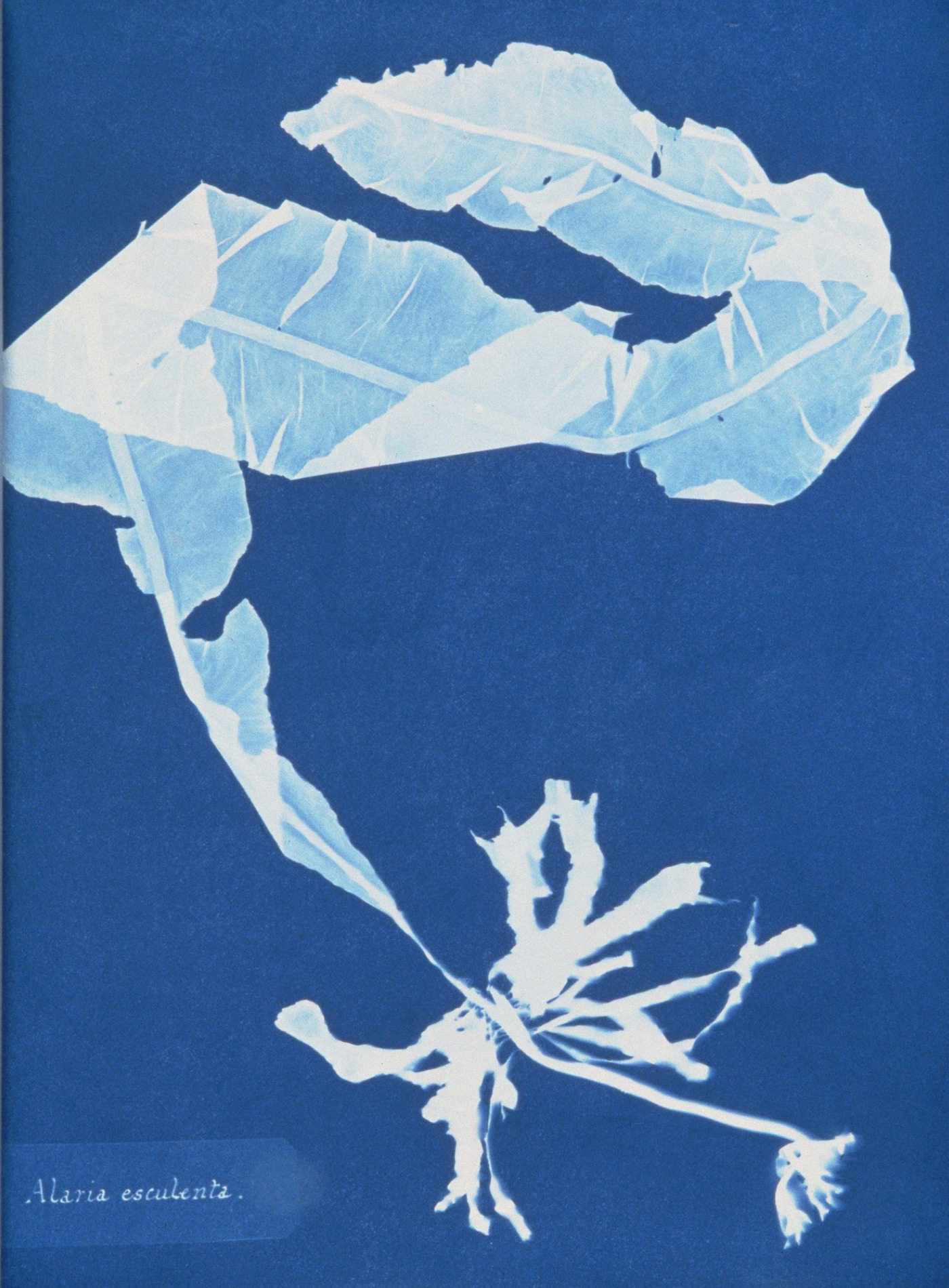

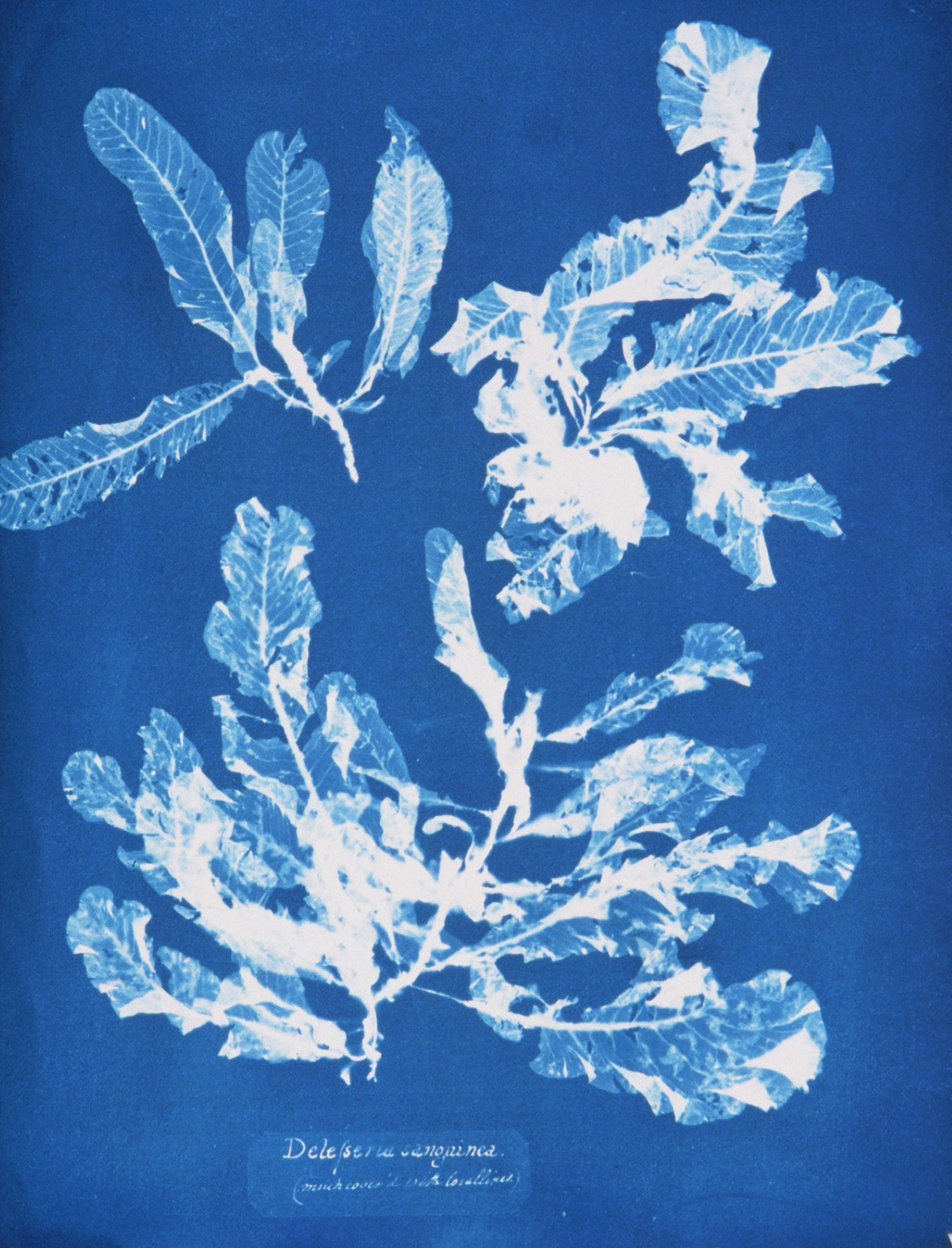

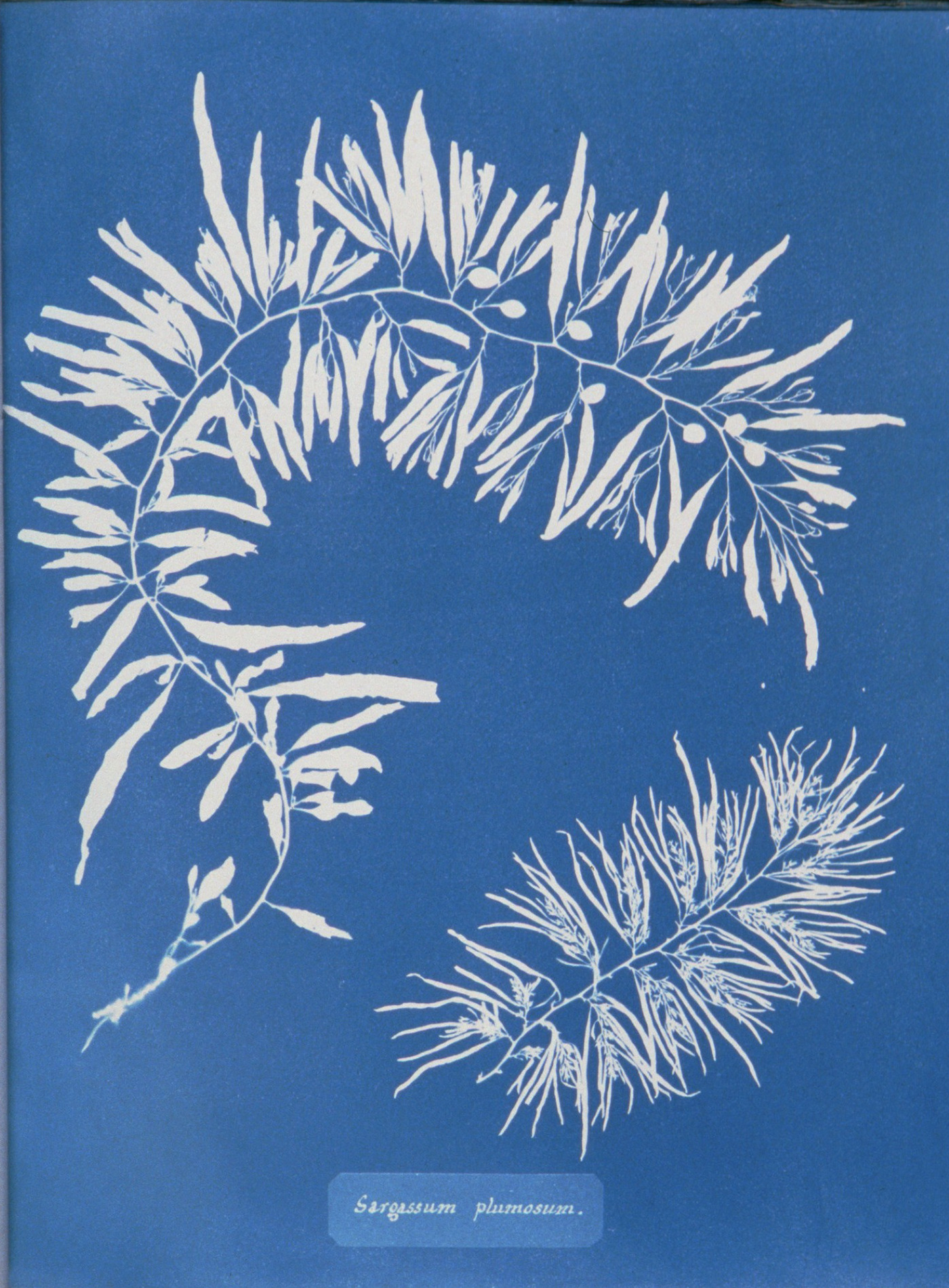

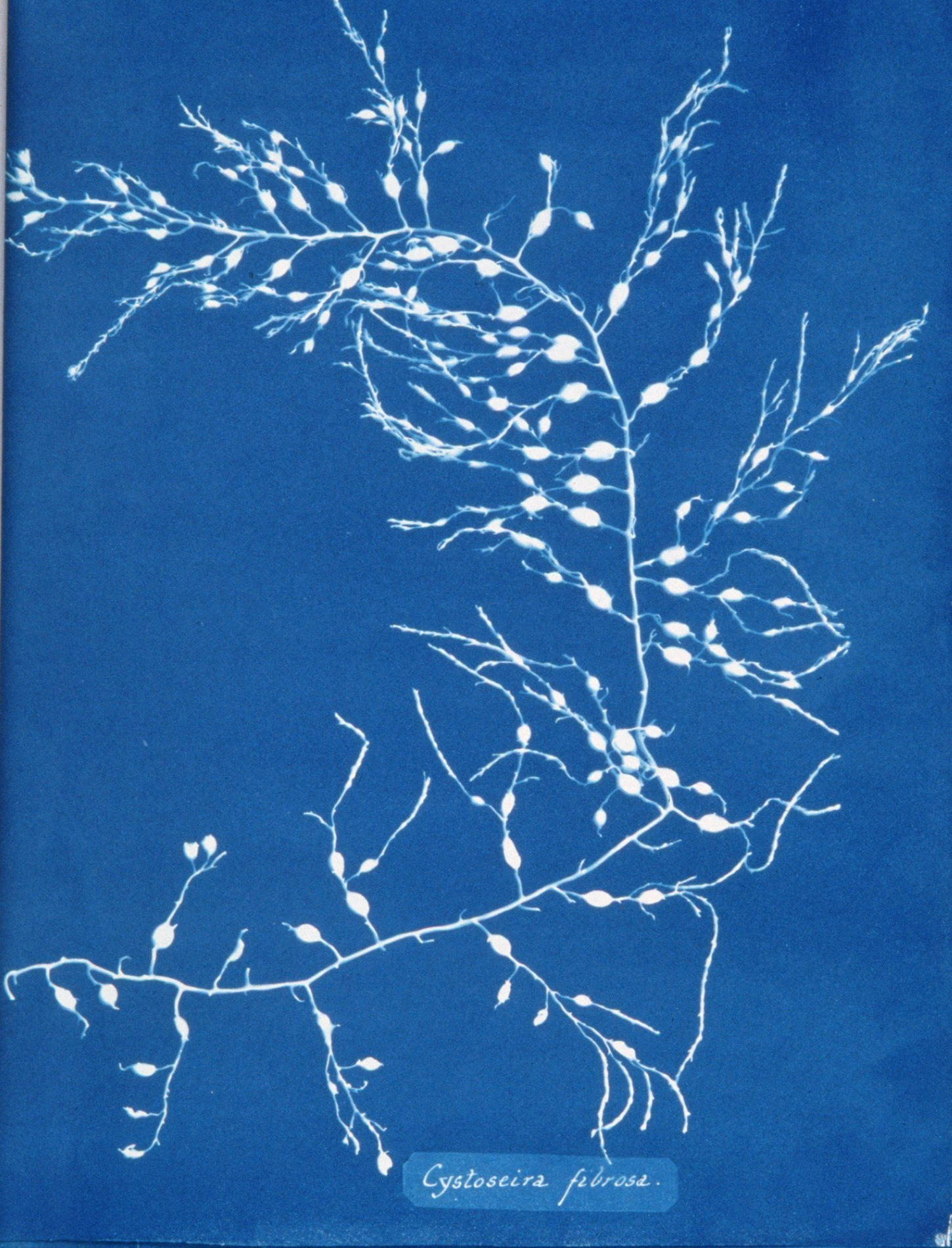

These diaphanous forms are the ghosts of algae. A Victorian woman named Anna Atkins conjured them using an early photographic technique called cyanotype. Her effort represents “the first realistic attempt to apply photography to the complex task of making repeatable images for scientific study and learning,” writes art historian Larry J. Schaaf in his book Sun Gardens: Victorian Photograms by Anna Atkins.

The polymath John Herschel—son of the astronomer William Herschel—first described the cyanotype process in 1842, three years after his friend William Henry Fox Talbot officially announced the invention of photography on paper. The method generally involves coating paper or other absorbent material with a mixture of iron salt (typically ferric ammonium citrate) and potassium ferricyanide; placing a flat item of interest on top of the paper and holding it in place under a piece of glass; exposing the entire assembly to sunlight for several minutes; and then rinsing the paper with water once the item has been removed. (For a DIY version, try this SciFri activity.)

The light-exposed portion of paper develops a pigment called Prussian blue (its chemical name is ferric ferrocyanide) while the subject appears silhouetted in white like a “cameo trace,” says Carol Armstrong, a professor of art history at Yale University, who curated a 2004 exhibit that focused in part on Atkins’s work. (For more on cyanotype, check out “Cyanomicon–History, Science and Art of Cyanotype: Photographic Printing in Prussian Blue.”)

From 1843 to 1854, Atkins created cyanotypes of more than 400 kinds of algae as part of a work called Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions. What’s more, she made numerous photographs of each specimen so as to produce multiple copies of her book. (Schaaf is aware of at least 12 surviving copies.)

“For that project alone, we’re looking at [a minimum of] 5,000 original photographic prints made on hand-coated papers, which is quite a bit of dedication,” says Schaaf, who is also the director of the William Henry Fox Talbot Catalogue Raisonné, part of Oxford University’s Bodleian Libraries.

As was customary of the era, Atkins produced and published her book in installments. With the release of her debut set in 1843, she became the first person to publish a book of photography, edging out Talbot by a year. (He published The Pencil of Nature in 1844.)

Atkins was born on March 16, 1799, in Kent, England. Details about her personal life are scarce, but surviving records suggest that she was an intellectual with “a great fondness for Botany,” writes Schaaf in Sun Gardens, quoting Atkins’s father, the chemist John George Children. Children was a fellow and a secretary of the Royal Society (the United Kingdom’s national science academy) and worked at the British Museum. His wife died after childbirth, and Children raised Atkins from infancy, undoubtedly fostering her scientific proclivities.

“Because of the closeness with her father, she would have had considerable contact with the scientific world, at least indirectly,” says Schaaf. That world included Hershel, who lived near her and her husband’s home later in life, as well as Talbot. Atkins was also a member of the Botanical Society of London, “which was one of the few societies that admitted women at the time,” says Schaaf.

Atkins’s work on algae was not her first foray into scientific illustration. In the 1820s, she drew by hand a series of seashells for her father’s translation of the French naturalist Jean-Baptiste Lamarck’s Genera of Shells. “They’re very beautiful drawings and very, very meticulous,” says Armstrong. Atkins was “a very good draftswoman.”

Algae drew Atkins’s attention as the subject was gaining scientific interest in Britain, according to Schaaf. She had her own fairly extensive collection, which included specimens that she had found and others that she received from friends. (During Atkins’s time, collecting botanical specimens was a popular pastime, and many amateur botanists were women.) According to Schaaf, Atkins intended to provide a visual companion to the botanist William Henry Harvey’s Manual of the British Marine Algae, published in 1841.

Atkins may have turned to cyanotype as a method of documentation for a few reasons. The technique was easier to manipulate and required less expensive chemicals than the photographic processes that Talbot had invented (he revealed another in 1841), which were silver-based, says Schaaf. Cyanotype also conveyed a greater sense of authenticity, because at the time, “each and every image came in direct contact with the specimen that it represented,” says Armstrong.

Perhaps the most obvious explanation, however, was that Prussian blue befitted her marine subject matter. “A blue background is both understandable and predictable,” says Schaaf.

British Algae is the only major work involving cyanotype from that time period, according to Schaaf, although the late 19th century would see others harnessing the blue-printing process for copying architectural plans and book-printing, among other purposes. As a form of botanical documentation, however, cyanotype never quite caught on. Because the technique only captured an object in silhouette, it didn’t provide as much information as “traditional engravings or etchings from drawings did,” says Armstrong.

And “the very strength of photography—its specificity, its accuracy—was actually a drawback,” says Schaaf. In botany, portraying a generalized representation of an organism rather than an exact replica of a single specimen was (and is) often preferable, and best achieved by hand, he says. For example, traits from several specimens of a given species can be blended, and unwanted detail omitted, in hand-drawn illustrations. (The idea extends beyond botany; see this SciFri article about fish illustration.)

In one respect, then, Atkins explored a technique “that is kind of a dead-end,” says Armstrong. But “even if it failed as a botanical work, [British Algae] certainly was a foundation stone in getting the idea of photographic illustration accepted,” says Schaaf.

“If we accept that this wasn’t a venture that had a great practical influence specifically, the idea of photography influencing scientific research and influencing other fields—of course it’s terribly important. And Atkins recognized the potential of that, and on her own, pulled it off, which I think is to be applauded,” he says.

Collectively, Atkins’s work can also be considered “a contribution to the history of photographic art,” says Armstrong, as evidenced by an exhibit on cyanotype called Cyanotypes: Photography’s Blue Period, on display at the Worcester Art Museum in Massachusetts. Atkins herself seemed to recognize the aesthetic appeal of her process: She also created cyanotypes incorporating subjects beyond algae, including ferns, feathers, and lace. In these works, “she very clearly is using the cyanotype expressively,” says Schaaf.

But many would also probably agree that her algae compositions are lovely to look at, even if sheer beauty wasn’t her original intent.

For more images, see the New York Public Library’s digital collection, Ocean Flowers: Anna Atkins’s Cyanotypes of British Algae.

*This article was updated on March 21, 2016 to reflect the following changes: An earlier version stated that Anna Atkins and her husband lived on a “homestead.” Larry J. Schaaf says that it’s unclear to him how big her property was at the time, so the term has been changed to “home.” Also, the exhibit at the Worcester Art Museum is called Cyanotypes: Photography’s Blue Period, not Botany’s Blue Period, as was previously stated.

Julie Leibach is a freelance science journalist and the former managing editor of online content for Science Friday.