Storytelling Teaches Robots Right and Wrong

12:03 minutes

Human children spend years in school and by their parents’ sides learning the rules of the game: how our culture works, how to be polite, and the difference between right and wrong. But robots? They know only what their instructions tell them to do, which is usually to accomplish a task as quickly and efficiently as possible. As a result, almost all of them demonstrate sociopathic tendencies.

Human children spend years in school and by their parents’ sides learning the rules of the game: how our culture works, how to be polite, and the difference between right and wrong. But robots? They know only what their instructions tell them to do, which is usually to accomplish a task as quickly and efficiently as possible. As a result, almost all of them demonstrate sociopathic tendencies.

In the real world, that might mean cutting in line, stealing, or other frowned-upon behaviors. So how do you teach robots to behave ethically, with good etiquette? In other words, how do you turn them into stand-up robotic citizens? One way is to feed robots human stories, and train them to model their behavior after the tales’ protagonists, according to Mark Riedl, associate professor at the Georgia Tech School of Interactive Computing.

Mark Riedl is a computer science professor and director of the Entertainment Intelligence Lab at Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta, Georgia.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow.

Kids spend years and years by your side. They’re in school learning the rules of the game, how our culture works, how to be polite, the differences between right and wrong.

But robots? We’re seeing more and more of them everywhere you look. And almost all of them are born with sociopathic tendencies, according to my next guest. They know only what their instructions tell them to do, which is usually accomplish a task as quickly and efficiently as possible.

But in the real world, that might mean, what, cutting in line, stealing, other not-so-friendly endeavors and behaviors. So how do you teach these robots how to behave ethically with good etiquette? In other words, how do you turn them into stand-up robotic citizens? That’s what we’re going to be talking about.

Give us a call. Our number is 844-724-8255. That’s 844-SCI-TALK. And, of course, you can tweet us @scifri.

Mark Riedl is an associate professor in the School of Interactive Computing at Georgia Tech in Atlanta. He presented his latest work last week at a meeting of the Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence, and it was in Phoenix. I’ll bet you didn’t even know there was an organization about the advancement of artificial intelligence. Welcome back to Science Friday.

MARK RIEDL: Hi. It’s a pleasure to be here.

IRA FLATOW: Well, what is this all about? The last time we talked, you were training robots to learn story plots and write fiction. And now you’re teaching them to behave like good citizens. And you’re doing this by analyzing stories, copying the protagonist behavior, is that right?

MARK RIEDL: Yeah, that’s right. So what we’ve been seeing over the last few years is really this kind of keen interest in the question of what happens when robots and other artificial intelligence agents, like Siri and Cortana, really start engaging with us on a more of a day-to-day, kind of social level.

And the question arises, are these going to be safe? Are they going to be able to harm us? And I don’t just mean in terms of physical damage or physical violence, but in terms of disrupting the social harmonies, in terms of, as you mentioned, cutting in line with us or insulting us. And what happens is when robots are trying to super optimize, they can do this quite unintentionally.

So what we wanted to do is we wanted to try to teach agents the social conventions, the social norms, that we’ve all grown up with and we all used to get along with each other. And the question became, how do we get this information into the computer, into the robots? They don’t have an entire lifetime to grow up and to share these experiences with us.

And we look at stories. And stories are a great way, a great medium, for communicating social values. People who write and tell stories really cannot help but to instill, in most parts, the values that we cherish, the values that we possess, the values we wish to see in good upstanding citizens in the protagonists, in the people that we talk about when we tell stories.

IRA FLATOW: Can you give me an idea of the stories that you’re reading to them or telling them.

MARK RIEDL: Well there’s kind of two different parts to this. There’s the long term vision where we imagine feeding entire sets of stories that might have been created by an entire culture, or an entire society, into a computer and having them reverse engineer the values out. So this could be everything from the stories we see on TV, in the movies and the book we read, really kind of the popular fiction that we see.

IRA FLATOW: But you must have to pick and choose between the kinds of moral stories and ethical dilemmas that you want. Because if you sit there and watch television, you’re going to think everything is about shooting and cups and robbers.

MARK RIEDL: Oh, yeah. Well that’s really kind of a good point. But cultures and societies are not monolithic, right. So there’s lots of different attitudes and interpretations that go into that. But when you look at an entire set of fiction that’s created by an entire society, there’s going to be such a huge amount that–

Well, what machine learning systems do, what artificial intelligence really is good at doing, is picking out the most prevalent signals, the most prevalent parts. So the things that it sees over and over and over again, time and time again, are the things that are going to kind of rise and bubble up to the top. And these tend to be the values that the culture and the society cherish.

So even though we see, say, TV shows now with antiheroes, that’s still a vast minority of the things that our entire society has output. So it’s going to pick up on the most common values that it sees.

And I would actually argue that we don’t want to cherry pick. Because by doing so, we run into the danger of unintentionally reinforcing certain behaviors. Whereas, the computer should pick everything out and find the things that it needs to find for itself.

IRA FLATOW: And so what do you train the robots or the computers in them to do? Give us an idea.

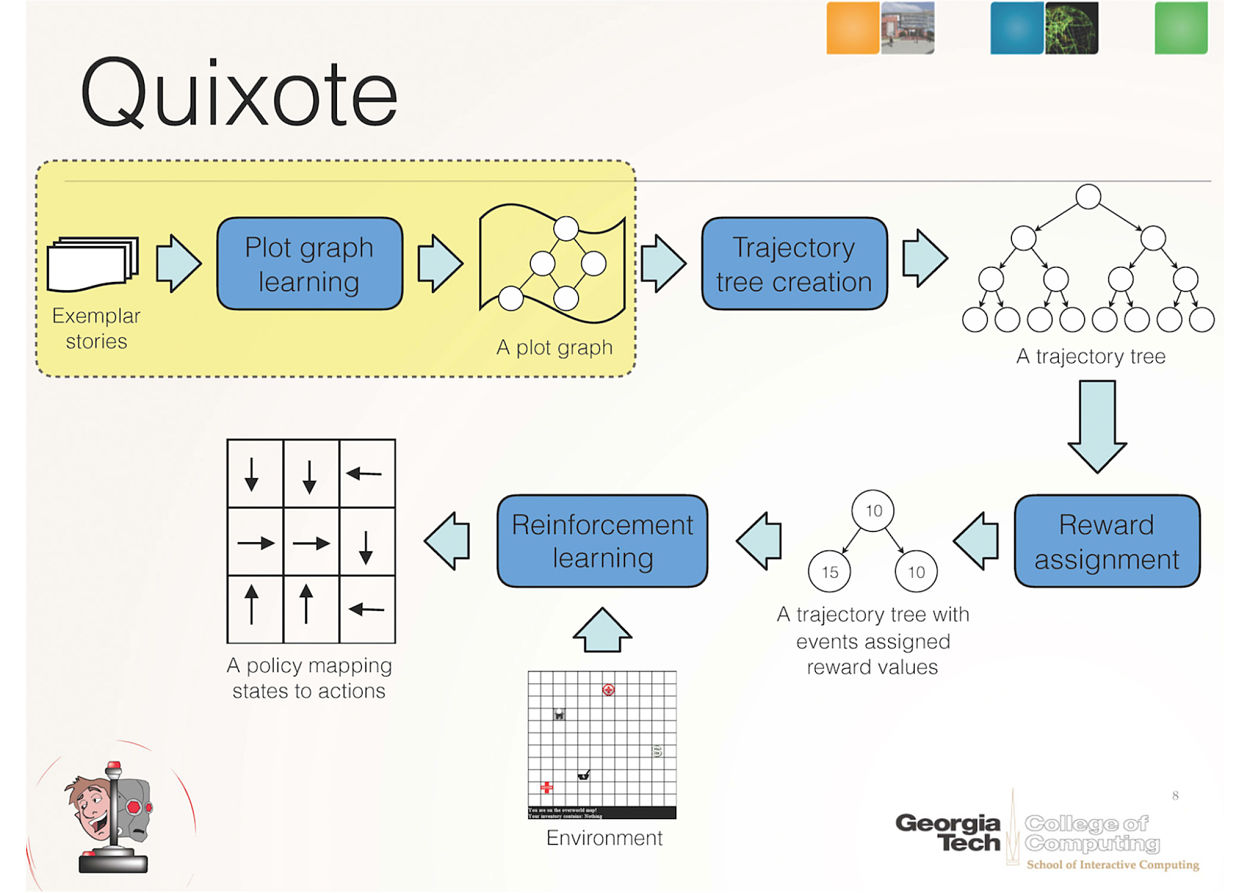

MARK RIEDL: Right. So at this stage of things, I’m working on a software artificial intelligence system called Quixote, which is named after the book by Cervantes. And we’re still in very early stages of the research.

So what we do now is we’re still giving the system very simple stories, very childlike stories, really kind of procedures. So here’s a story about how you catch an airplane. Or here’s a story about how you might pick up your groceries or pick up a prescription drug from a pharmacy. And they’re somewhat literal, you know. John walks to the bank. John withdraws the money. John stands in line waiting for the teller. Those sorts of things. Because those are stories that are a little bit easier to understand.

But what it turns out is, when you ask people to tell stories even that simple, they tend to tell the computer what should happen, what the computer should expect to happen along the way. And, again, these kind of encode the quote unquote “right” way of doing things, the ways that they would choose to do it, the things that kind of innately bypass the negative results. Meaning that they don’t steal, they stand in line, they’re polite to people, so on and so forth.

IRA FLATOW: So you’re actually putting your moral and ethical values into the robot.

MARK RIEDL: Well whomever we choose to tell the stories to the robot. So we chose stories not only because they’re very good at conveying the social values. Again, authors really innately can’t help but to encode their own values into the actions of the protagonist. But also stories are very easy to tell. So virtually anyone could program a robot or program an agent in AI simply by telling stories. We don’t have to teach people how to teach computers.

IRA FLATOW: But just as humans can make cultural faux pas in different countries, wouldn’t we also need to tailor robots to the culture that they are living in?

MARK RIEDL: Absolutely. And that’s a really great point. So different societies do have different social conventions that they follow. They are sometimes very different, sometimes very superficial. So if we want to deploy a robot or an agent in any sort of society, we would really need to go to that society and collect the stories that come from that society. So it’s learning to kind of be immersed in that culture, in that society. So we definitely want to see different versions of these agents and artificial intelligences for different parts of the world, for example.

IRA FLATOW: In the movie Ex Machina, Ava, the robot, is trained by using big data, big Google searches. Of course, spoiler alert, the outcome is not so good. Did you consider this kind of method instead of just storytelling?

MARK RIEDL: Well, what we’re actually doing is working towards a big dative approach. But instead of taking all the data in the world, what we want to say is, let’s focus on stories, because those are where the values of a culture are going to manifest themselves more correctly.

So if you want to say, people who tell stories are not objective. It’s not, you know, all the financial records of a complete society which might lead you towards a more super rational sort of decision making process. There’s personality, there’s behavior.

Really, if you want to think about stories writ large, they’re examples of how to behave in society. Stories have everything from meeting with another character in a restaurant, and the social protocol you go through there, to exemplifying the moral standards of, let’s say, trying to save the universe.

IRA FLATOW: And, on the other hand, there’s the story of Bernie Madoff that is a different kind of story that reflects real life.

MARK RIEDL: Yes. But when you think of protagonists as being those characters that exemplify the things that we see as the best parts of our society, antagonists, or the bad guys, are the opposite, and they kind of get their just desserts. So you should be able to, in theory, learn that certain behaviors lead to negative outcomes.

IRA FLATOW: Are there any bedtime stories, as a better way of putting, because it sounds like you’re starting on childhood level with the robots, that you could point out to us that you tell the robots?

MARK RIEDL: Yeah. Well, I think children stories are great place to start because they do tend to convey some of the simpler social constructs we have and some of the simpler values and morals we have.

My son is two and 1/2 years old right now, and he loves to watch a TV show called Peppa Pig. In every episode of Peppa Pig, the protagonist goes out to do something new. Goes on a field trip the first time to a ski slope, and what to expect, what you do when you get to a ski slope, and the things that follow from there.

And there’s usually some sort of moral about making a right choice versus a wrong choice as well. And combined with the fact that this is simpler language, I think there’s a lot that we can learn very immediately these children sorts of stories.

IRA FLATOW: Do you teach the robots that story?

MARK RIEDL: We’re still at a simpler stage yet. Natural language processing is very hard. Story understanding is hard in terms of figuring out what are the morals and what are the values and how they’re manifesting. Storytelling is actually a very complicated sort of thing. We’re just now starting to look at corpora, or sets of children’s stories now.

IRA FLATOW: I’m sure you get a lot of suggestions from people about what stories to tell your robots.

MARK RIEDL: Oh, yeah. Everyone has their favorite stories. But I do think at the end of the day, the artificial intelligence has to look at all the stories and make the judgments themselves, to basically say, lots of these stories are repeating the same themes, and those themes are more important than the ones that are not repeated.

IRA FLATOW: So right now you’re at a very early stage. You’re not reading them the Harvard book shelf, or that kind of stuff, or even children’s stories, but trying to figure out what the best, simple ones are.

MARK RIEDL: Yeah, and right now we have a very explicit storytelling model. Right now we’re looking at agents that can do one thing at a time. So we have an example of an agent that we want to teach to go to and pick up prescription drugs at a pharmacy. So what we do is we tell it a number of stories about different things that might happen on the way to do that.

So right now the artificial intelligence is not a general artificial intelligence. It is not going out and doing lots of different things. It has this one specific task. But we want to make sure it’s going to do that task in the right way, that it is going to follow the conventions of society.

IRA FLATOW: Why call it Quixote, Don Quixote?

MARK RIEDL: Yes. So when we were trying to decide a name for the system, we looked at the classic novel by Cervantes. And the Don Quixote character in the book by the name was a fictional character who was reading stories about medieval knights. And then he decides to adopt the chivalrous values of the knights and actually start acting like those knights and going out and having adventures. So we thought, here’s a character who is learning a set of values from a set of stories. What a great name for our computer.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. That is great. We wish you great success with it, and come back and tell us about your results.

MARK RIEDL: I’d look forward to doing that.

IRA FLATOW: Mark Riedl, associate professor in the School of Interactive Computing at Georgia Tech. He’s a Ramblin’ Wreck from Atlanta. Thanks for being with us today.

Copyright © 2016 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of ScienceFriday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies.

Christopher Intagliata was Science Friday’s senior producer. He once served as a prop in an optical illusion and speaks passable Ira Flatowese.