Human Embryo Gene Editing Gets Go-Ahead in U.K.

12:04 minutes

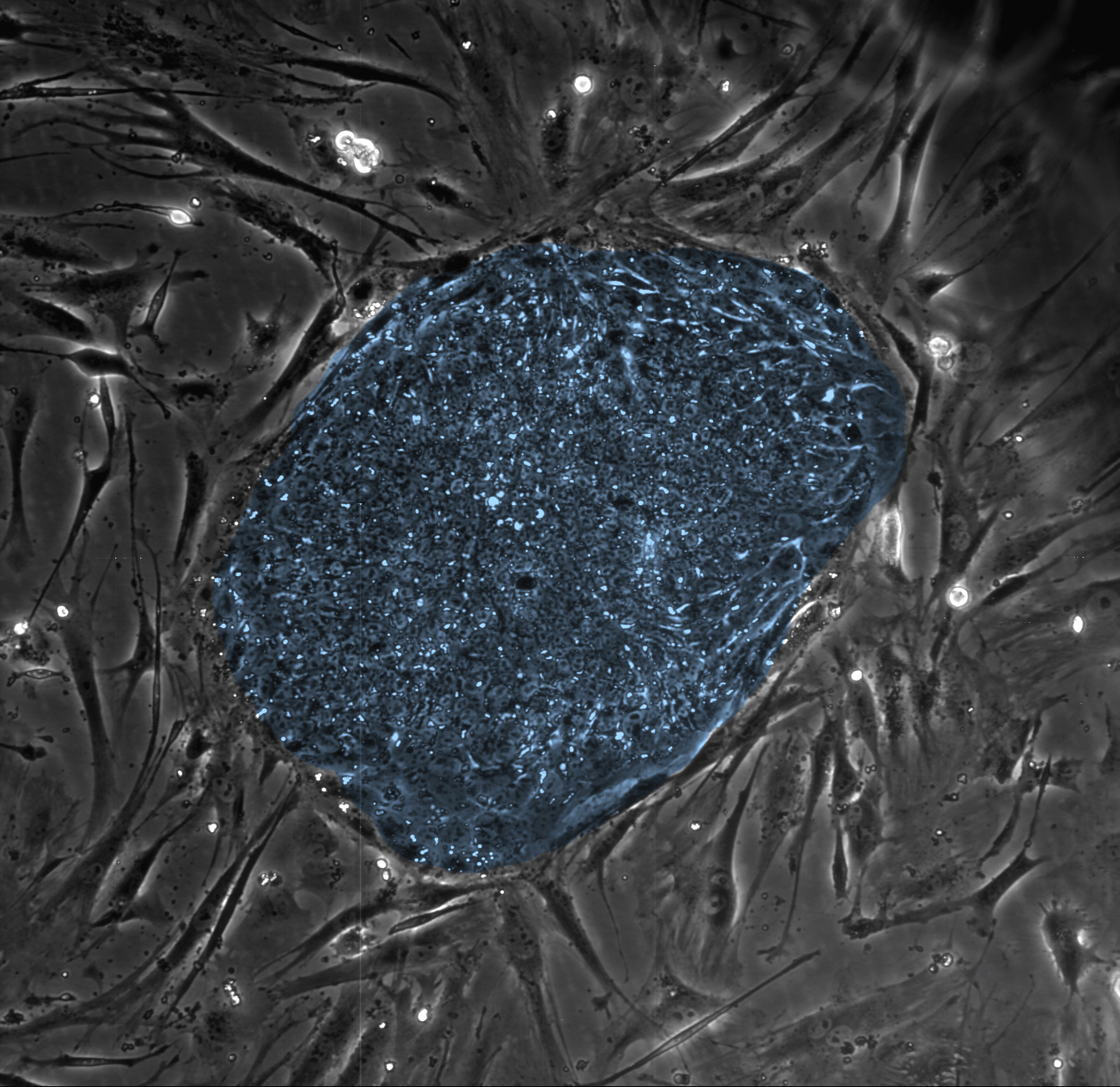

This week, the U.K.’s Human Fertilization and Embryology Authority gave scientists the green light to use the CRISPR-Cas9 gene-editing technique in human embryos. The scientists will not be using the method for any direct therapeutic purpose, but instead will investigate the genes that guide human development. Stem cell biologist George Daley and bioethicist Hank Greely discuss the scientific, legal, and ethical aspects of the decision.

George Q. Daley is a Harvard Medical School professor and director of the stem cell transplantation program at the Children’s Hospital and Dana Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, Massachusetts.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. This week, the United Kingdom’s Human Fertilization and Embryology Authority, the HFEA, gave scientists the green light to edit the genes of human embryos, using the technique known as CRISPR/Cas9. Even though the scientists will be destroying the embryos they experiment on, with no intention to implant the embryos, some critics have called it the first steps towards designer babies. Possible? Or, as one of my next guests, Hank Greely, has said, “Should we simply keep calm and CRISPR on?”

What do you think? Our number is 844-724-8255. Joining me to demystify the science behind this experiment, before we get into the ethical and legal conundrums, is George Daley. He’s a professor at Harvard Med School and director of the Stem Cell Transplantation Program at Boston’s Children’s Hospital. Welcome back, Dr. Daley.

GEORGE DALEY: It’s good to be here, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s talk a bit about how this process works, about what the scientist, Kathy Niakan, and her lab want to do.

GEORGE DALEY: Yeah, well it takes advantage of this incredibly powerful new technique called CRISPR. It’s essentially a bacterial immune system that’s been adapted for use in human cells. Just like we are bombarded with viruses, bacteria has developed a way of fighting off viruses. They recognize the invader and chop it up. So scientists have been able to adapt this to human cells in a way that allows us to, very specifically, identify a gene, recognize it, and either chop it up, deleting its activity, or repair it, a process we call gene editing. What Dr. Niakan now wants to do is employ this very powerful method for gene editing in human embryos.

IRA FLATOW: Well, can’t we just study this in mice, like we do other things?

GEORGE DALEY: Well, mice aren’t people. We really can’t answer the critical questions about human development in mice. It turns out that mice develop differently. The principles we’ve discovered in mice don’t seem to work in humans. So Dr. Niakan really wants to address very critical questions in human development. And this is going to shed important light on questions like infertility, miscarriages, and birth defects.

IRA FLATOW: And it’s something you can only do when you study it in humans.

GEORGE DALEY: That’s right. That’s right.

IRA FLATOW: And the CRISPR is very well known, isn’t it? It’s widely used now.

GEORGE DALEY: It’s only been described about three years ago for its applications. And yet, it’s now swept the international biomedical community. I mean, virtually every laboratory is taking advantage of this. It’s so powerful, so efficient, and so easy to use that it’s finding all sorts of very exciting new applications.

IRA FLATOW: I’d like to bring on another guest. Hank Greely is a law professor at Stanford and director of the Center for Law and the Biosciences there. Welcome back, Hank.

HANK GREELY: Thanks for calling me.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s talk about the regulatory body in the UK, the HFEA. How much wiggle room is there in their authority to use this technology? I mean, in terms of it being misused.

HANK GREELY: Well, HFEA has broad power over really all assisted reproduction in the UK. We have nothing like it in the United States. And if you do something that they haven’t allowed you to do, or do something against the rules they set down, you can be punished. Just because something is illegal doesn’t necessarily mean that it won’t happen. But when you’re regulating something like IVF clinics, these are people with licenses and businesses and something at stake to lose. So I’m not aware of anyone intentionally violating HFEA procedures.

IRA FLATOW: Is there a feeling worldwide that this is pretty– that doctors are going to do what they say they are doing and not trying to experiment bringing human embryos to term?

HANK GREELY: Yeah, I don’t think there are a lot of mad scientists in this field. I think most mad scientists are in movies and in books.

GEORGE DALEY: Yeah. I mean, we– the scientific community has really come out very strongly in favor of regulation and self-policing in this area. We had a Global Summit sponsored by the Chinese Academy of Sciences, the United States Academy, and the United Kingdom Academy, that was held in Washington in December. And our organizing committee really endorsed the need for the research that we’re talking about today, that’s been approved in the UK, as long as it remained laboratory-based. Because applying gene editing to embryos for clinical use, say for IVF, or for bringing a baby to term, isn’t sanctioned. And there’s been really a broad call for caution and prudence in the scientific community.

HANK GREELY: And really, when you think about trying to make a baby using a previously unknown technique, the potential downside is enormous. The idea of bringing seriously disabled or deformed or dead children into the world is a serious constraint. There are legal ramifications. There are medical licensure ramifications. The woman who’s a necessary part of it would have to consent to it. It doesn’t mean that it’s impossible, that at some strange corner of the world, somebody might try something inappropriate. But I think it’s not very likely. Dealing with humans, making babies with humans, comes with lots of inherent constraints that, say, work with non-humans does not.

IRA FLATOW: Mm-hmm. And is Great Britain the first country to OK to do this? Have the Chinese used CRISPR on human embryos?

GEORGE DALEY: They have, yes. It first occurred in China. There was, in fact, a paper that was published reporting the first experience with editing human embryos. And it was, in part, that paper that stimulated a strong interest in the scientific community to get out ahead of this, to establish guidelines, and to make sure that the work is being done with the proper kind of thoughtful oversight, and that it’s not being moved prematurely into clinical use. So the UK, under this HFEA authority, they’ve really established a very high standard. And they’ve ensured that this project has real scientific merit, and that’s why it’s been approved.

HANK GREELY: The Chinese regulatory authorities were involved, as we understand it, in that original study. Their regulatory system is a little more opaque than ours. And I think one of the good things that may come out of the CRISPR Summit in December is a little more discussion and transparency back and forth between different countries about their regulatory systems.

One of the really nice things about the Chinese experiment is they used embryos that could not become babies, embryos that had been fertilized by two sperm, and even if you tried to put them into a woman’s womb, they could not lead to a pregnancy and a birth. The research that was approved by the HFEA is using normal embryos, but with the requirement that the lab not transfer them into a woman for possible birth.

IRA FLATOW: Mm-hmm. You don’t see the US, the FDA, OKing any kind of research like this in the near future, do you, Hank?

HANK GREELY: It’s actually illegal right now, in a funny sort of way. Congress decided to ban all funding for FDA to even consider this kind of thing. Ironically, when they first tried it, they did it in a way that would have backfired. They said, FDA can spend no money to consider any such proposal. But the way FDA works when it’s approving research, if you submit a research application called an Investigative New Drug exemption application, or an IND, it goes into effect unless the FDA blocks it in 30 days.

Ultimately, for this year’s appropriations bill, or appropriations for NIH and FDA, Congress said, not only can’t they spend any money, but any such application will deemed not to have been received. So since they never receive it, the 30-day timetable can’t start. That’s an appropriations rider. It lasts for one year. But for that year, FDA will not be able to issue any INDs allowing researchers to try this with respect to putting it into humans, to try this in terms of making babies. The non-clinical work– the work that George and I have been talking about and the work that the HFEA approved– doesn’t go through FDA at all. Because it doesn’t involve giving a new drug or device to a human being.

IRA FLATOW: So who would it go through?

HANK GREELY: Basically, almost nobody in the United States.

IRA FLATOW: So you could try it yourself, if you want.

HANK GREELY: You coudn’t try it with federal funding. Federal funding is not available.

GEORGE DALEY: There’s a real distinction here. I mean, there’s a distinction between what you can use your federal grant dollars to study, which is certainly not this, and what is at least permissible under private funds. And there is now underway a process that the International Society for Stem Cell Research is going to put forth. And it’s a set of guidelines that really govern the conduct of human stem cell research and embryo research. It’s been widely discussed. We’ve presented it in draft form this past summer. It will be released probably in March or April.

And like the HFEA, it’s going to lay out a set of ethical standards and responsible practices, so that this type of very important research can, in fact, be done. It will have to be approved by very rigorous processes, institutional review, and oversight. But we do hope that this work gets done in the United States. It will have to be done with private funding. But it’s essential. and it’s going to teach us a tremendous amount about the earliest days of human development.

IRA FLATOW: And what about treating diseases? Some diseases are just ready for this kind of research?

GEORGE DALEY: Well, the research we’re talking about right now is laboratory-based. It will be targeted at problems– not really diseases, but conditions like miscarriage and infertility. And so it will have an effect there and it is valuable. Now, the longer term questions that arise is whether this technique could ever be used to eradicate disease in an embryo. That is, to prevent a baby from coming into the world with a particular disease. Could we treat it at that embryonic stage?

Now, there are some who think that’s a very laudable goal. But it also raises this thornier question of modifying human heredity. If we intervene in an embryo and cure a disease in an embryo, that means that that person’s offspring–

IRA FLATOW: It gets passed on.

GEORGE DALEY: –would also carry this genetic change.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. We’ve run out of time.

GEORGE DALEY: And that’s very, very controversial.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, you can see the ethical problems there. Hank Greely, law professor at Stanford, and George Daley, professor at Harvard Med School, thank you both for taking time to be with us today.

HANK GREELY: My pleasure.

GEORGE DALEY: Thanks for your interest.

Copyright © 2016 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of ScienceFriday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies.

Christopher Intagliata was Science Friday’s senior producer. He once served as a prop in an optical illusion and speaks passable Ira Flatowese.