The Bodybuilder: Oliver Sacks’ Days on Muscle Beach

The renowned neurologist remembers his bodybuilding days on Venice, California’s Muscle Beach.

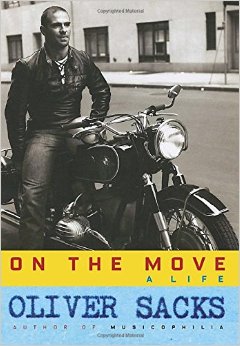

The following is an excerpt from On the Move: A Life by Oliver Sacks, which is the winter selection for the #SciFriBookClub. Learn more about this month’s book club here.

The following is an excerpt from On the Move: A Life by Oliver Sacks, which is the winter selection for the #SciFriBookClub. Learn more about this month’s book club here.

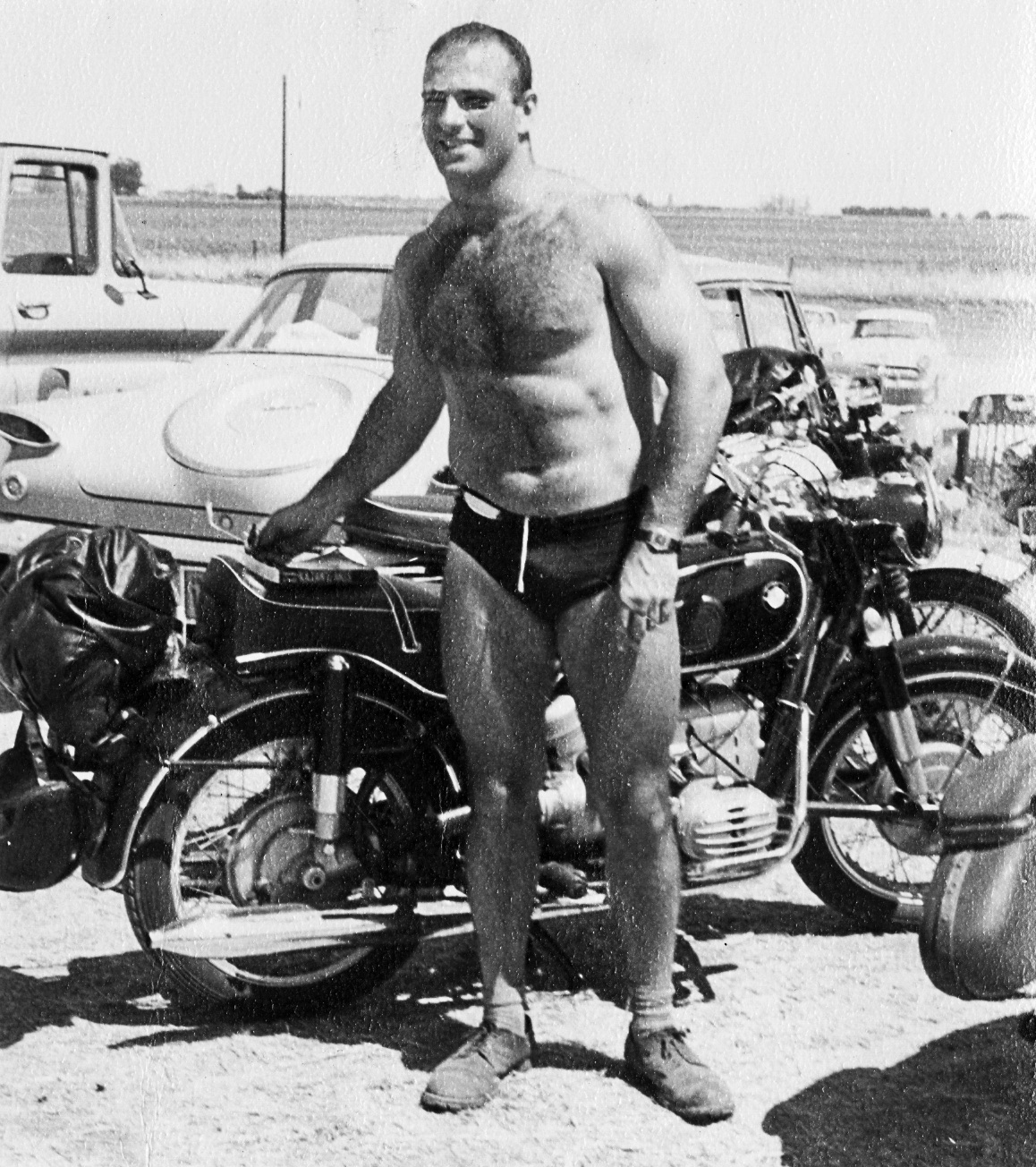

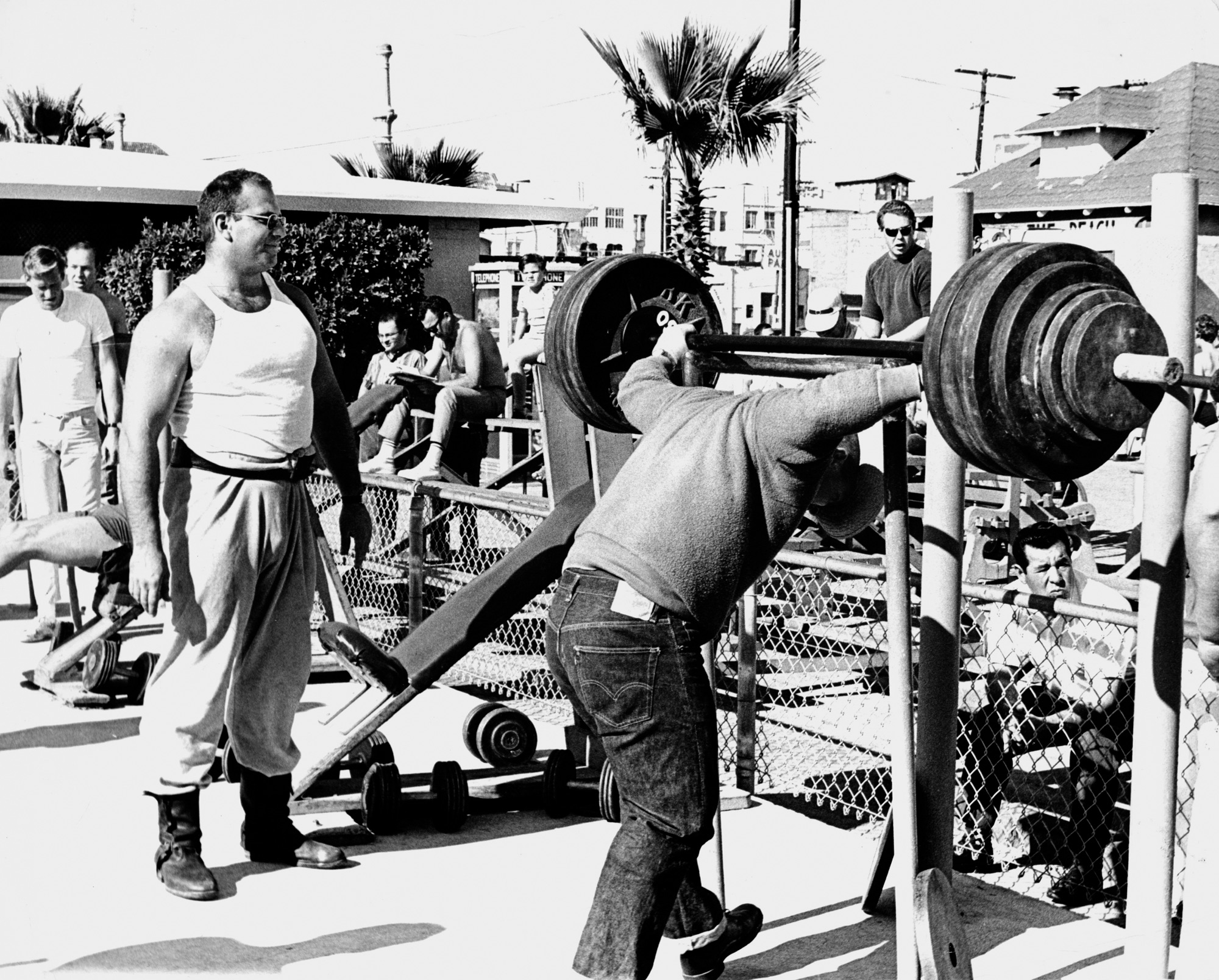

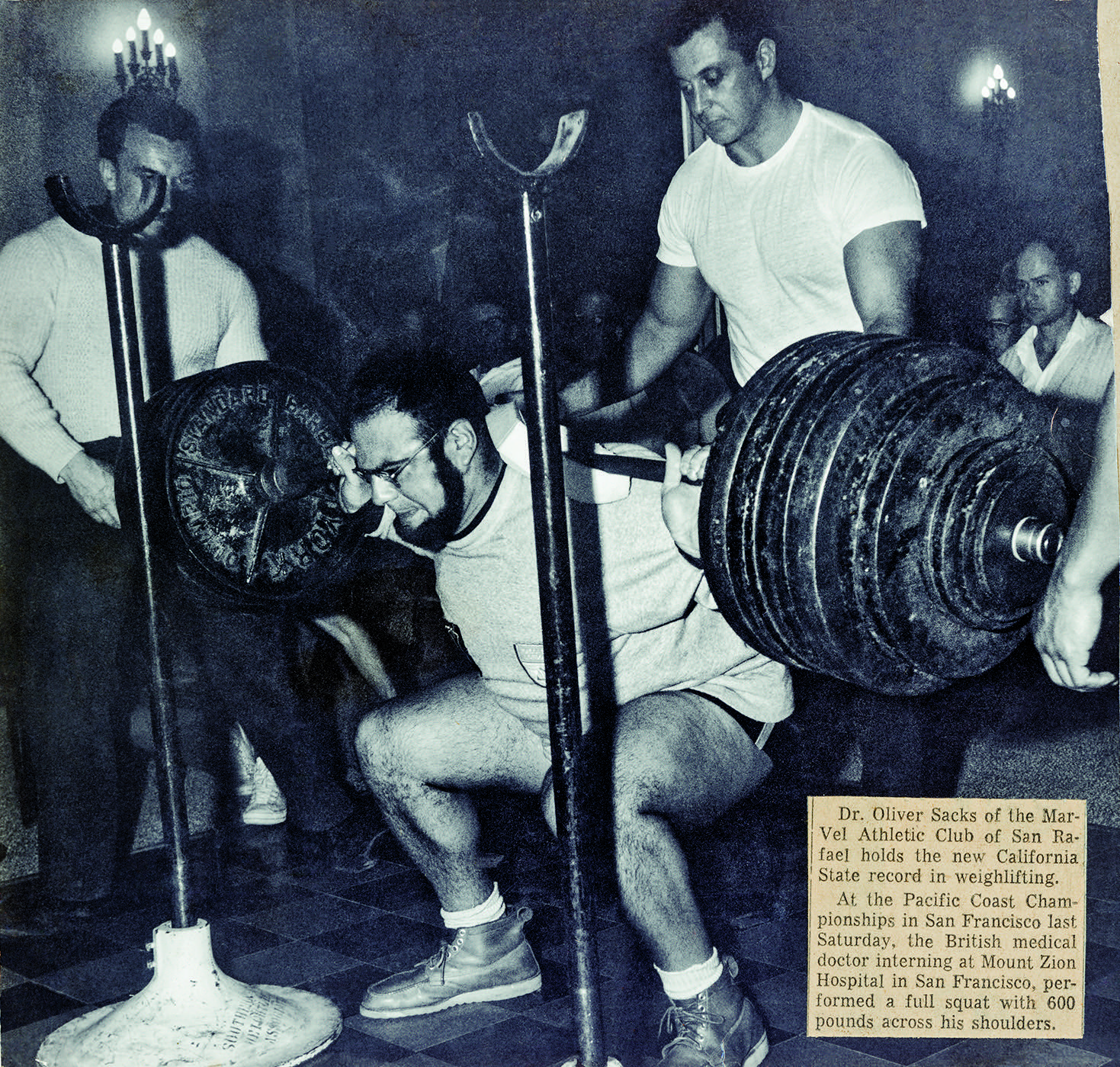

I got an apartment near Muscle Beach in Venice, just south of Santa Monica. Muscle Beach had many greats, including Dave Ashman and Dave Sheppard, who had both lifted in the Olympic Games. Dave Ashman, a cop, had a modesty and sobriety very much the exception in a world of health nuts, steroids takers, drinkers, and braggarts. (Although I was taking plenty of other drugs in those days, I never took steroids myself.) I was told he was unmatched at the front squat, a much harder and trickier lift than the back squat, because one is holding the bar in front of one’s chest rather than across one’s shoulders, and one must maintain perfect balance and erectness. When I went one Sunday afternoon to the lifting platform on Venice Beach, Dave looked at me, the new kid, and challenged me to match him in the front squat. I could not decline the challenge; this would have branded me a weakling or a coward. I said, “Fine!” in what was meant to be a strong, confident voice but came out as a feeble croak. I matched him pound for pound, up to 500, but thought I was finished when he went from 500 to 550. To my surprise—I had hardly ever done front squats before—I matched him. Dave said that was his limit, but I, with a vain-glorious impulse, asked for 575. I did this—just—though I had a feeling my eyes were bulging and wondered fearfully about the blood pressure in my head. After this, I was accepted on Muscle Beach and given the nickname Dr. Squat.

There were many other strong men on Muscle Beach. Mac Batchelor, who owned a bar to which we all flocked, had the largest and strongest hands I had ever seen; he was the world’s undisputed arm-wrestling champion, and it was said that he could bend a silver dollar with his hands, though I never saw this. There were two gigantic men—Chuck Ahrens and Steve Merjanian—who had a semi-divine status and were somewhat aloof from the rest of the Muscle Beach crowd. Chuck could do a one-arm side press with a 375-pound dumbbell, and Steve had invented a new lift—the incline bench press. Each of them weighed close to three hundred pounds and sported massive arms and chests; they were inseparable companions and completely filled the VW Beetle they shared.

Huge though he was, Chuck was eager to become even huger, and one day he appeared suddenly, filling the entire doorway, while I was working in neuropathology at UCLA. He had been wondering, he said, about human growth hormone—could I show him where the pituitary gland was located? I was surrounded by pickled brains, and I pulled one out of its jar to show Chuck the pea-size pituitary at the base of the brain. “So that’s where it is,” said Chuck, and, satisfied, took his leave. But I was disquieted: What was he thinking of? Had I been right in showing him the pituitary? I had fantasies of his raiding the neuropathology lab, going to the brains—a little formalin would not deter him—and plucking out their pituitaries, as one might pluck blackberries, and, even more gruesome, of his initiating a string of bizarre murders, in which the victims’ heads would be cracked open, the brains torn out, and the pituitaries devoured.

Then there was Hal Connolly, an Olympic hammer thrower whom I often saw in Muscle Beach Gym. One of Hal’s arms was almost paralyzed and hung loosely from his shoulder in a “waiter’s tip” posture. The neurologist in me instantly recognized this as an Erb’s palsy; such palsies come from traction on the brachial plexus during delivery if, as sometimes happens, a baby presents sideways and has to be pulled out by an arm. But if one of Hal’s arms was useless, the other was a world-beater. His athleticism was a moving lesson in the power of will and compensation; it reminded me of what I sometimes saw at UCLA—patients with cerebral palsy and little use of their arms who had learned to write or play chess with their feet instead.

I took photographs on Muscle Beach, trying to catch its many characters and their haunts; this went hand in hand with a project for a book about the beach—descriptions of people and places, scenes and events, in that strange world which was Muscle Beach in the early 1960s.

Whether or not I could have written such a book, a montage of descriptions and verbal portraits interlarded with photographs, I do not know. When I left UCLA, I packed all my photographs, everything I had taken between 1962 and 1965, along with my sketches and notes, in a large suitcase. The suit- case never arrived in New York; no one seemed to know what had happened to it at UCLA, nor could I get an answer from post offices in L.A. or New York. So I lost almost all the photographs I had taken in my three years near the beach; only a dozen or so somehow survived. I like to imagine that the suit- case still exists and that it may turn up one day.

There were occasional weekends when I was on call at UCLA and others when I supplemented my meager income by moonlighting at the Doctors Hospital in Beverly Hills. On one occasion there, I met Mae West, who was in for some small operation. (I did not recognize her face, for I am face-blind, but I recognized her voice—how could one not?) We chatted a good deal. When I came to say good-bye to her, she invited me to visit her in her mansion in Malibu; she liked to have young musclemen around her. I regret that I never took up her invitation.

Once my own strength came in handy on the neurological wards. We were testing visual fields in a patient unlucky enough to have developed a coccidiomyces meningitis and some hydrocephalus. While we were testing him, his eyes suddenly rolled up in his head and he started to collapse. He was “coning”; this is the rather mild term used for a terrifying event in which, with excessive pressure in the head, the cerebellar tonsils and brain stem get pushed through the foramen magnum at the base of the skull. Coning can be fatal within seconds, and with the speed of reflex I grabbed our patient and held him upside down; his cerebellar tonsils and brain stem went back into the skull, and I felt I had snatched him from the very jaws of death.

Another patient on the ward, blind and paralyzed, was dying from a rare condition called neuromyelitis optica, or Devic’s disease. When she heard that I had a motorbike and lived in Topanga Canyon, she expressed a special last wish: she wanted to come for a ride with me on my motorbike, up and down the loops of Topanga Canyon Road. I came to the hospital one Sunday with three weight-lifting buddies, and we managed to abduct the patient and lash her securely to me on the back of the bike. I set out slowly and gave her the ride in Topanga she desired. There was outrage when I got back, and I thought I would be fired on the spot. But my colleagues—and the patient—spoke up for me, and I was strongly cautioned but not dismissed. In general, I was something of an embarrassment to the neurology department but also something of an ornament—the only resident who had published papers—and I think this might have saved my neck on several occasions.

I sometimes wonder why I pushed myself so relentlessly in weight lifting. My motive, I think, was not an uncommon one; I was not the ninety-eight-pound weakling of bodybuilding advertisements, but I was timid, diffident, insecure, submissive. I became strong—very strong—with all my weight lifting but found that this did nothing for my character, which remained exactly the same. And, like many excesses, weight lifting exacted a price. I had pushed my quadriceps, in squat- ting, far beyond their natural limits, and this predisposed them to injury, and it was surely not unrelated to my mad squatting that I ruptured one quadriceps tendon in 1974 and the other in 1984. While I was in hospital in 1984, feeling sorry for myself, with a long cast on my leg, I had a visit from Dave Sheppard, mighty Dave, from Muscle Beach days. He hobbled into my room slowly and painfully; he had very severe arthritis in both hips and was awaiting total hip replacements. We looked at each other, our bodies half-destroyed by lifting.

“What fools we were,” Dave said. I nodded and agreed.

Excerpted from On the Move: A Life, by Oliver Sacks. Copyright © 2015 by Oliver Sacks. Excerpted by permission of Knopf, a division of Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Listen to Oliver Sacks read another excerpt from On the Move:

Oliver Sacks is the author of Musicophilia (Knopf, 2007) and a professor of neurology at the NYU School of Medicine in New York, New York.