Will a ‘Godzilla El Niño’ Put a Dent in the Drought?

12:10 minutes

The Los Angeles River has once again come to life, supercharged with rainwater. Freeways have flooded. And California’s Sierra Nevada—the so-called “snowy mountains”—are living up to their name. But is this “Godzilla El Niño,” as JPL climatologist Bill Patzert calls it, enough to put a dent in the drought? The answer may have to wait. Because, despite the big splash recent precipitation has made with residents of the West, current snowfall numbers are just about average, says JPL snow hydrologist Tom Painter. In this segment, Ira talks with Patzert and Painter about the outlook for the drought.

Bill Patzert is a Climatologist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California.

Tom Painter is principal investigator for the Airborne Snow Observatory at Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California.

IRA FLATOW: This is “Science Friday”. I am Ira Flatow.

The Los Angeles River has finally come to life, supercharged with rainwater. Freeways have flooded. In California’s Sierra Nevada, the so-called “snowy mountains,” are once again living up to their name. But is this Godzilla El Nino, as my next guest calls it, raining down literally enough to put a dent in the drought out there? Or are residents of the West just so unaccustomed to seeing water and snowfall from the sky that they’re getting their hopes up about what may turn out to be just average amounts of precipitation?

Are you seeing the effects yourself? Give us a call, 844-724-8255. Or tweet us @scifri.

Bill Patzert is a climatologist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena. Welcome to “Science Friday.”

BILL PATZERT: Wow, This is a great pleasure.

IRA FLATOW: Oh, the pleasure is all ours. Give us the scoop on El Nino. How big is it shaping up? And I understand from looking at the weather reports that you have a train of storms coming in.

BILL PATZERT: Well, this El Nino has been building for more than a year now. And this week it’s finally came to fruition here in California where we did see a series of storms, almost like a conveyor belt, and we had our first really good soaking in almost five years. And so there’s a lot of excitement. It’s been pretty sweet.

IRA FLATOW: I remember when I was out in California that’s all they talked about was, we’re going to be saved this drought by the El Nino on the way.

BILL PATZERT: Well, not so quick. This is what I call a down payment on a drought with a huge mortgage to pay off. Big El Ninos only happen every 15 to 20 years. So when you look over the long haul, El Ninos only supply about 7% of our water supply. And so it’ll take more than that to get us out of this punishing drought.

IRA FLATOW: Weather forecast out there looks pretty clear in the next few weeks. Do you expect more of these storms rolling on in?

BILL PATZERT: Well, January, February and March in 1998– the last big El Nino– we had to wait till February, but when it arrived it was spectacular. So everybody has to be a little patient here. This is a huge signal out there in the Pacific, and if it doesn’t deliver record rainfall and snow pack, I’ll definitely have to go into witness protection.

IRA FLATOW: [LAUGHING]

How long do you expect it to last, typically? How long does the El Nino let it rain out there?

BILL PATZERT: Well, you know El Nino– and let’s not forgot it’s had a huge impact over the rest of the planet– pretty spectacular. Here in California and the West in the southern tier of the United States, it’s January, February, March and sometimes into April and May.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, because I’ve heard people explaining our mild winter on your El Nino.

BILL PATZERT: Well, that’s the El Nino signal is the southern tier of the United States gets blasted with a series of storms from California to Florida, whereas the northern tier of the United States tends to be relatively mild and warmer. So the headlines are mudslides in Los Angeles and golfing in Minneapolis.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, and they like that out there in Minneapolis.

Just so you don’t have to go alone by yourself into witness protection, I’m going to bring on another guest, a person who may have one of the most picturesque jobs in America. He flies over beautiful mountain ranges all over the American West using a laser to measure the snow pack that you’re talking about. Tom Painter is a snow hydrologist at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena. Welcome to “Science Friday”.

TOM PAINTER: Thanks for having me.

IRA FLATOW: Tom, you’re up in Lake Tahoe right now, right? What’s it like up there?

TOM PAINTER: Well, it’s a spectacularly gorgeous California bluebird day, but everybody appears ecstatic with the amount of snow. And as you said in the intro, people’s minds have gotten a little bit tweaked into thinking that average conditions are the great messiah of snow for us now. And so it is wonderful seeing this amount of snow, but we do need to recognize that right now we’re about spot on with average conditions for this time of year.

IRA FLATOW: So then would you expect that you will have an average amount of water from the snow pack for next summer? There’ll be adequate amounts like you would have in an average condition.

TOM PAINTER: Well, if it keeps lumbering along like it is right now, then yeah, we would just end up with average conditions. But Bill has promised that this El Nino is going to produce in a big time just like 1998 and 1983, and I’ll ship him off into the Witness Protection Program–

IRA FLATOW: [LAUGHING]

TOM PAINTER: If it doesn’t come to bear. But we’re pretty confident. Statistically, it should produce the big storms that we’re hoping for that will really make it leap up above average conditions.

And back in ’98 and in ’95 here in the Sierra Nevada, the snow pack up in the higher elevations was continuing to grow at the beginning of June. Now usually our peak is around April 1, but this conveyor belt of storms can continue on out through the spring, and you can see no let up at times when it’s really determined to dump on the mountains.

IRA FLATOW: How much could it potentially? If this conveyor belt continues, how much more snow, and would it then really become something to talk about?

TOM PAINTER: These are the kind of storms that change the face of the landscape. I mean buildings get buried, large buildings get buried, and huge trenches have to be dug out for roads and for ski lifts. And in 1998 the campgrounds up in upper Yosemite National Park never opened because of the amount of snow. So it can be towering amounts of snow, and hugely beneficial for recharging the aquifers, getting the ground water back toward where we need it. But as Bill said, this is a down payment. We’ve got a long ways to go. We need a lot of precipitation to bring us back, not only for the groundwater, but also for the reservoirs.

And the ecosystems themselves, we’ve lost an enormous amount of the forests in the Sierra Nevada, simply because of this ongoing drought and the intensity of that drought.

IRA FLATOW: Bill, could we expect it to hang around for another year– next year come back– and dump some more water and snow?

BILL PATZERT: Well that’s a long shot. After the last El Nino, we whip lashed back into a condition which is known as La Nina, where the waters in the equatorial Pacific get very cool, and I’m very fond of calling a La Nina The Diva of Drought. And so the thing we have to be careful with here is that a year from now we might be doing this interview talking about drought.

IRA FLATOW: I’m booking it right now.

ALL: [LAUGHTER]

IRA FLATOW: I’m not hoping that we’ll talk about drought, but just the opposite of the El Nino. But I guess people are enjoying it even as it rains too much and snows too much. They’re happy to see it.

TOM PAINTER: I certainly am. I was out on my front porch the other morning drinking my coffee, and it was fantastic. It was coming down an inch to a half an inch an hour, and it was pretty exciting and sweet.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. Well, Bill, if our water supply is shrinking and the population is growing, should we take a cue from folks who know about droughts, like in Israel and Australia– the vanguards of water conservation– take a lesson or two from them– is there anything we can learn from them?

BILL PATZERT: The population in California has quadrupled in the last half century. Agriculture has expanded and a whole series of new industries have developed, so people forget that half of this drought is too many people using too much water in a semi-arid environment. But the good news is we’ve developed a lot of conservation habits here during this drought. And people should not forget that it’s not temporary, that is the new lifestyle, or we’ll be talking about drought forever.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, well at least for this year the Sierra Nevadas, the so-called “snowy mountains,” are at least this year living up to their name.

BILL PATZERT: Yeah, I’ve been concerned that Painter will be out of business.

TOM PAINTER: [LAUGHING]

BILL PATZERT: But it looks like he’s still on his feet and–

ALL: [LAUGHTER]

BILL PATZERT: Having a good time there in Lake Tahoe.

ALL: [LAUGHTER]

IRA FLATOW: What’s it like to go up in a plane and zap the mountains with a– Tom– with a laser beam, and see all that stuff?

TOM PAINTER: It is really amazing, and it was much of the reason that I moved to the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, so we could do this for our community. We’ve long wanted to know how much total water there was up in the mountain snowpacks, but we as a community have been pretty much using the same technology that was developed 100 years ago just at the north end of Lake Tahoe here by a professor from the University of Nevada Reno. And in large part because traveling in the mountains is hard, it’s dangerous from the altitude and from avalanches, and then we discovered a few years ago that we could put together a combination of technologies that have been used on Earth as well as in the solar system to map all across the mountain basins and add up actually how much water there is.

So no longer do we need to say, oh, there’s 110% of plus or minus 20, 30 percent, we can actually say how much water is in the mountain snowpack which is really what water managers want to know and what the critical number is. So this has been a breakthrough, and we were fortunate to be at the right time with the right motivation to get this going. Drought helped highlight this, and and we’re really hoping to have a massive El Nino so that we can measure gobs of snow.

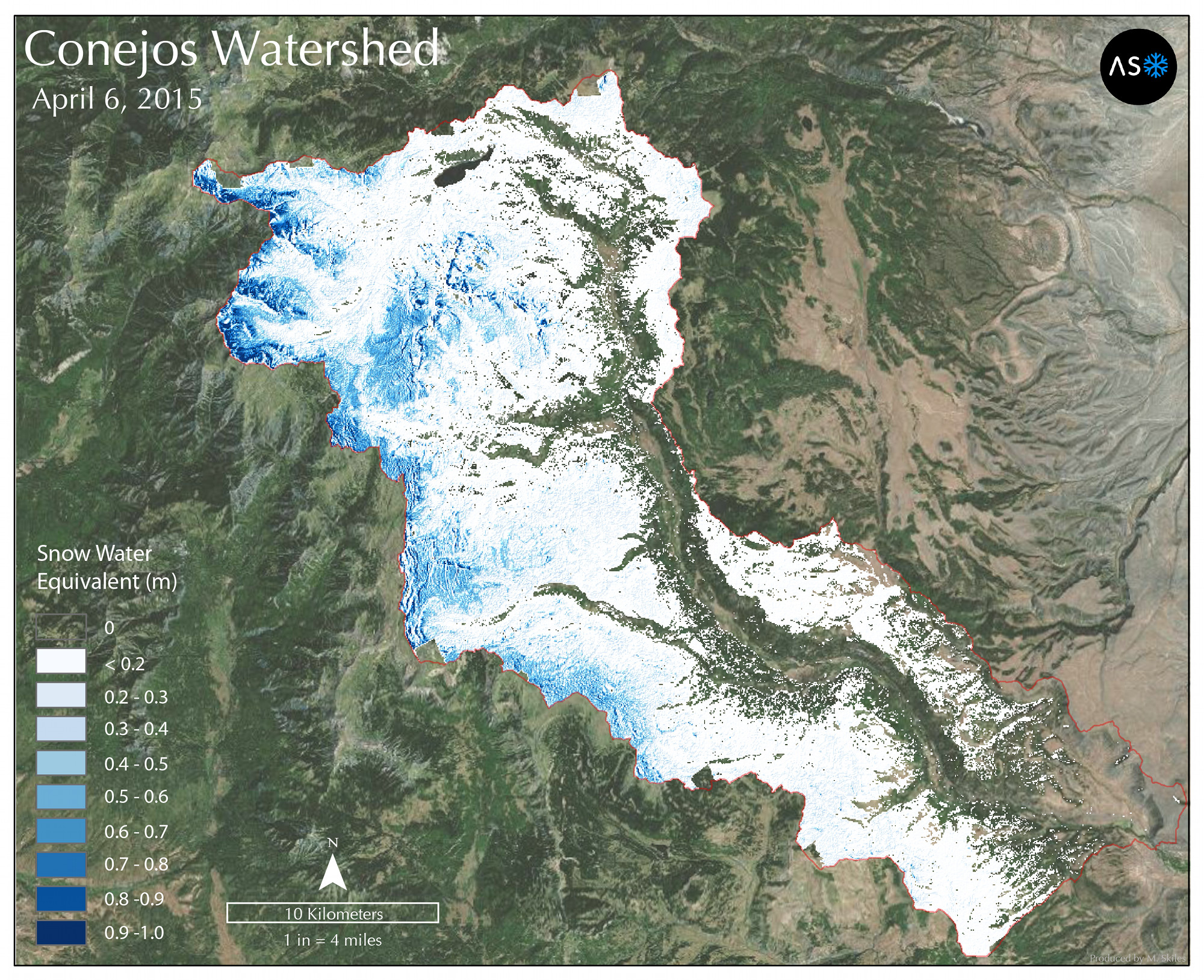

IRA FLATOW: We have a bird’s eye view of Tom’s airborne snow survey. You can fly over to www.ScienceFriday.com/snowpack to see it.

Gentlemen, thank you very much for taking time to be with us today.

Copyright © 2016 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of ScienceFriday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies.

Christopher Intagliata was Science Friday’s senior producer. He once served as a prop in an optical illusion and speaks passable Ira Flatowese.