Building A ‘Beest’ Fit For The Beach

Dutch artist Theo Jansen has spent 25 years constructing massive sculptures designed to crawl, scuttle, and stride along the beach.

Jansen wrangles a strandbeest, Animaris Apodiacula, on the beach in 2013. Courtesy of Theo Jansen/photo by Uros Kirn

There’s a moment that gets Dutch artist Theo Jansen excited—the moment when you catch sight of one of his kinetic “strandbeest” sculptures out of the corner of your eye. “If you see a strandbeest moving there [in your peripheral vision], you see an animal,” he says, “but it’s just a bunch of tubes.”

“Strandbeest” is a portmanteau of the Dutch words for “beach” and “beast.” Designed for traversing the sandy shores of Jansen’s native Scheveningen, Netherlands, his “beests” range in size from the diminutive 5-foot long Animaris Ordis to the 42-foot-long monster, Animaris Suspendisse. However big or small, strandbeests operate fundamentally the same way: Wind hits a sail, pushing the beest forward along an array of rotating “legs” connected via a central crankshaft. While Jansen constructs his beests from the humblest of materials—each “skeleton” is a collection of PVC pipe and plastic tubing, bound together with zip ties—the results are uncannily lifelike. Depending on whom you ask, a strandbeest on the move might resemble a bleach-white horse, gingerly picking its way across the sand, or a massive undulating caterpillar.

That eerie animal quality is by design. For the past 25 years, Jansen has been hard at work attempting to create something like a living creature: a machine so well-adapted to its coastal environment that it can navigate the shoreline without Jansen’s supervision—and perhaps even after he’s gone. It’s a quixotic goal, one that the artist describes with obvious devotion, and a wink. “I’m working on this ideal,” he says, “to make a new specimen for the world before I leave the planet.”

Strandbeest Animaris Ordis strides along the beach, driven by a wind-sail. Courtesy of the Peabody Essex Museum

Jansen’s quest began in 1990. By then, he had abandoned studies in physics to pursue painting and writing, and he shared a “fantasy” with his readers in an offbeat column for the Dutch newspaper De Volkskrant. The idea, he remembers now, was that “I would build sort-of skeletons which would walk on the wind and gather sand to build up dunes, to protect the country from sea level rise.” The idea languished until that September, when Jansen was passing by a tool shop. “I bought some of these tubes [PVC pipes], and then I played for an afternoon with the tubes,” he says. “At the end of the afternoon, I decided to spend one year on the tubes. And that was 25 years ago.”

The roving sculptures that descended from those first tube experiments—today’s strandbeests—are far from the dune-constructing machines of Jansen’s fantasy. They don’t shore up beaches. But over the years, Jansen has improved the beests’ design. Slight modification by slight modification, in an incremental process inspired by Darwinian evolution, he’s made them better equipped to survive their coastal environment.

Strandbeest Animaris Percipiere (2005). The storms that roll into Scheveningen in the autumn put the strandbeests’ adaptations to the test. Courtesy of Theo Jansen/photo by Loek van der Klis

“The usual cycle of an animal is that I build a beest in the spring, and I bring it to the beach,” Jansen explains. “And then the whole summer I am doing all kinds of experiments on the beach.” In a given summer, Jansen might tackle a single problem hindering the beests’ ability to survive—say, their tendency to walk straight into the waves—by creating a range of potential modifications.

Design innovations that help the beests successfully navigate Scheveningen’s sand and storms are retained. Those that don’t are eliminated. Over the course of a summer, the strandbeests’ shape morphs until fall, when Jansen is ready to declare that year’s generation “extinct.” (“They go into the boneyard,” he says.) Traits that helped that summer’s beests survive carry over into next year’s beests. “I hope to combine all these methods and strategies [for survival] in one animal at the end, so it can survive all circumstances,” Jansen says.

The Making of Suspendisse

One of Jansen’s largest-scale strandbeests, Animaris Suspendisse, navigates the beach. Courtesy of the Peabody Essex Museum

So far, the beest to come closest to fulfilling Jansen’s dream of a self-sufficient, roving sculpture is a 12-foot-high behemoth named Animaris Suspendisse.

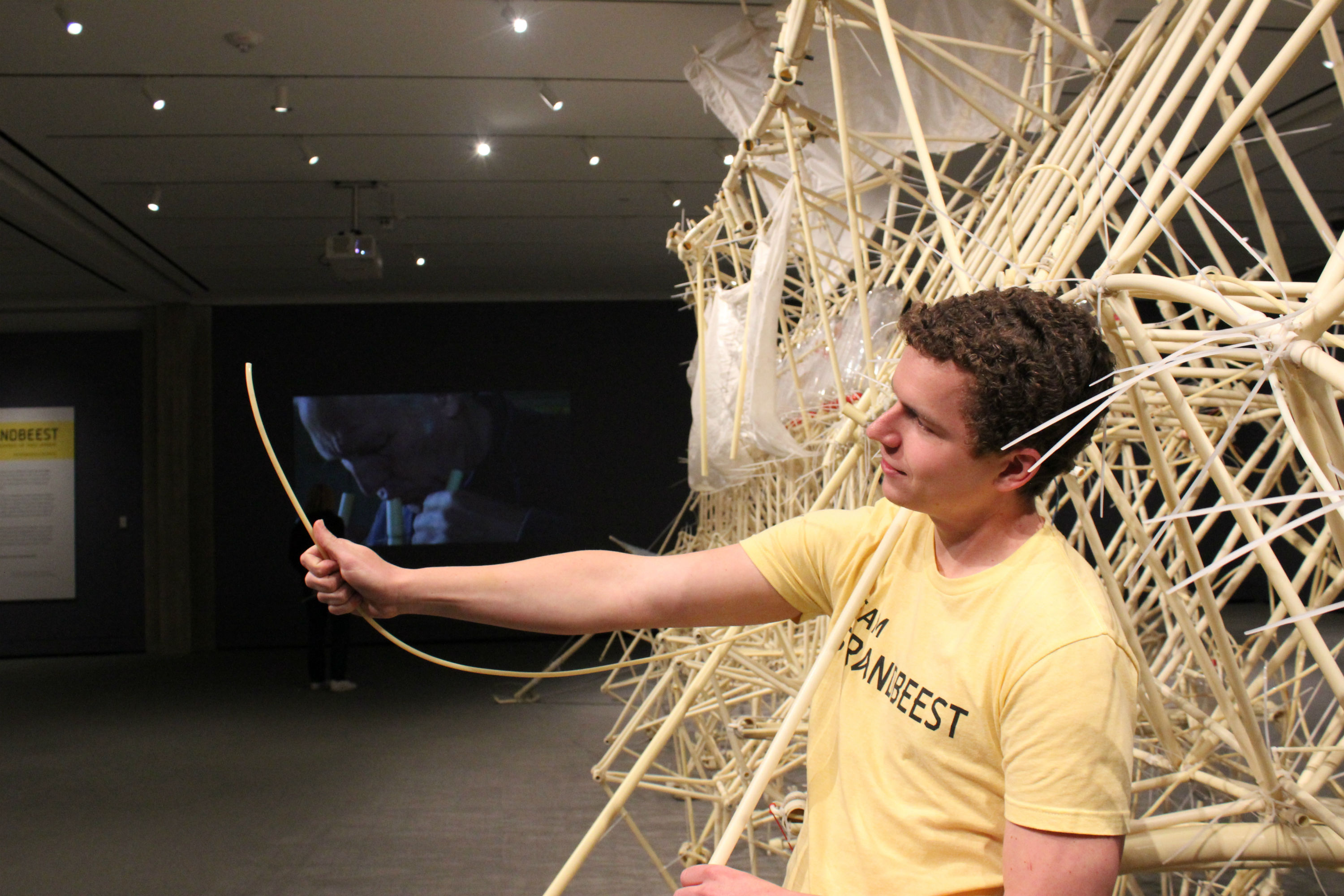

Combining many of the features of previous beests, Suspendisse is something of a superbeest. It’s undoubtedly the centerpiece of a new exhibition of Jansen’s work currently on view at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts. (The exhibition will travel to Chicago and San Francisco in 2016). “Strandbeest: The Dream Machines of Theo Jansen” successfully condenses 25 years of strandbeest evolution, thanks largely to the efforts of the museum’s corps of strandbeest “interpreter/operators.” Trained by Jansen, the interpreter/operators roam the exhibition, putting Suspendisse into motion (with compressed air rather than wind) and fielding a constant stream of questions from curious visitors.

When I visited the exhibition in mid-October, interpreter/operator Jonathan Talit was on hand to walk me through some of the adaptations that make Suspendisse Jansen’s top beest on the beach.

1. Wind Stomachs

As wind-walkers, strandbeests face one very big problem: what to do when there’s no wind? To answer that question, Jansen devised a system of “wind stomachs” that propelled previous generations of strandbeests in windless conditions. He’s carried this “adaptation” over into Suspendisse’s design.

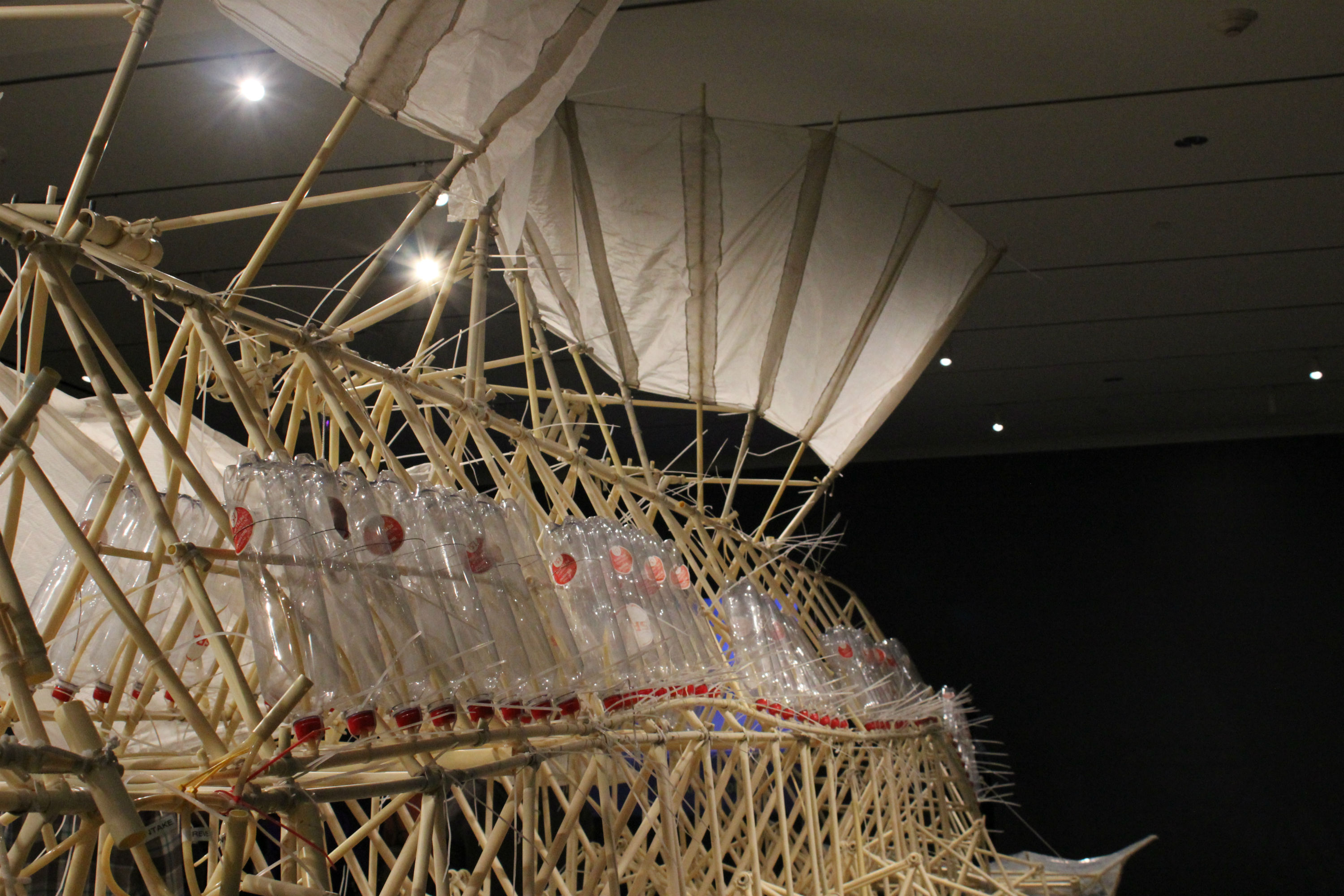

Suspendisse’s topsail funnels air into its “wind stomachs” (1.5 liter plastic bottles). Photo by Annie Minoff

“[The stomachs’] first function is to act as a battery and a backup” by storing air, Talit explains. Suspendisse’s wind stomachs are rows of 1.5-liter plastic bottles that line its upper half. As wind pushes the beest’s undulating topsail, pistons pump air into these bottle-stomachs just “like a bike pump,” Talit says. The compressed air that builds up inside is power the beest can draw on to walk without wind. (Suspendisse’s wind stomachs can handle up to 85 pounds per square inch of air pressure.)

Solving the problem of air storage did something else, too: It allowed Jansen to transform his beests into pneumatic systems. By connecting his power source (the wind stomachs) to different components along the beest’s body via a system of medical tubing, Jansen created a way to use air pressure changes to trigger different beest “behaviors,” such as changing direction and lifting its body slightly off of the sand. That breakthrough led to a bevy of new beest “adaptations,” many of which Jansen included in Suspendisse’s design.

2. “Ski Poles”

This adaptation—which Jansen has playfully dubbed “ski poles”—allows Suspendisse to drag itself forward using only compressed air. When triggered by a change in air pressure, Suspendisse’s powerful pistons pop out a series of seven long PVC “poles” which, fully extended and planted in the sand, drag the beest forward. (Imagine a Nordic skier pulling himself along a track on his poles. Suspendisse uses its “ski poles” in much the same way.) “It will take a big lurch step forward, like this strandbeest is skiing towards you really quickly,” Talit says.

3. Nose Feeler

Survival for a strandbeest often comes down to one thing: avoiding the ocean. “Especially with the winds coming from the land, they tend to walk into the sea, and they drown very easily,” Jansen says. The nose feeler’s job is to keep that from happening by detecting hard sand. (Where there’s hard sand, there’s bound to be water.)

Suspendisse’s nose feeler sits on the end of its ponderous proboscis, which curves down just enough so that the feeler lightly touches the ground. The feeler is constructed from two tubes, one of which collapses into the other when pressure is applied to it. “If [the nose feeler] hits fluffy sand, there’s not a lot of pressure acting on it,” Talit explains. “But if it hits hard sand, it will clamp completely up.” When the first tube collapses into the other, it cuts off airflow to a portion of the beest’s network of medical tubing, triggering Suspendisse’s “ski pole” mechanism and propelling the beest away from a watery death.

4. Water Feeler

Suspendisse’s water feeler is yet another protection against drowning. “It’s just a big piece of medical tubing” that drags along the ground, Talit says.

Jonathan Talit holds out Suspendisse’s “water feeler” for inspection. Photo by Annie Minoff

As long as this length of tubing remains dry, air can flow through it. But as soon as the tube is dragged into water, air can no longer flow freely—it’s blocked by water. As with the nose feeler, this creates a change in pressure that triggers Suspendisse’s ski pole mechanism, causing the beest to heave itself out of the water.

5. Sweat Glands

Suspendisse’s latest adaptation is nothing less than a system to help it schvitz. (And it doesn’t get much more animal than that!) Working on the beach, Jansen had to contend with sand creeping into his beests’ joints. Now, he says, “before the animal starts walking, it sweats and washes all the sand [out].”

One of Suspendisse’s sweat glands, filled with strandbeest sweat (soapy water). Photo by Annie Minoff

Suspendisse’s sweat glands are plastic soda bottles filled with soapy water. These are connected to the beest’s system of medical tubing, which runs all along its body. As the beest’s topsail flaps back and forth in the wind and the wind stomachs “breathe in” air, it creates a pressure disequilibrium that forces the sweat glands’ soapy water up through the system of medical tubing, towards the beest’s most sand-prone parts (like the backs of the knees). As Talit puts it, “The strandbeest will rinse itself from the inside out.”

Dune-Builders

Jansen admits it will take many more adaptations like these before Suspendisse’s “descendants” can stalk the beaches of Scheveningen without his help. Right now, “I have to nurse them all the time,” he says. “The storms are quite skilled at destroying them.” There are a lot of problems to solve, he accedes, “but they can be solved.”

Jansen already has his sights set on the next problem he’ll tackle. “When there’s a storm, the [strandbeest’s] feet are buried in sand,” he explains. He’s working on a system that would lift the beest’s body up off of the ground slightly every hour, shaking the sand off of its feet in the process.

If it works, Jansen notes, this perpetual sand-shedding will also have a side effect: “[The beest] will grow a hill under it,” he says. He’s reminded of the fantasy that originally inspired his strandbeest project—a dune-building creature that could protect the Netherlands from rising seas.

“So finally, maybe,” he says, “[the strandbeests] will build dunes on the beach.”

Annie Minoff is a producer for The Journal from Gimlet Media and the Wall Street Journal, and a former co-host and producer of Undiscovered. She also plays the banjo.