Solar Wind Strips Martian Atmosphere, Diamond Dirt, and the Whole Story on Milk

12:02 minutes

Mars today is a dry husk of its once liquid water-supporting self, and scientists have been studying how the Martian climate could have changed so drastically. This week, NASA’s Mars Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution (MAVEN) mission offered up a clue: solar wind, which strips gas from the Martian atmosphere. MAVEN also revealed that when solar storms occur, the rate at which the Red Planet loses gas from its atmosphere increases. The Verge’s Arielle Duhaime-Ross discusses these findings, as well as a new theory on diamond formation and other short subjects in science this week.

Plus, whole milk has long been relegated to the category of unhealthy saturated fats. The U.S. Department of Agriculture, for example, recommends consuming fat-free or low-fat milk instead. But do we really have the whole story on the potential benefits or drawbacks of whole milk? The Washington Post’s Peter Whoriskey joins Science Friday to talk about the good and bad of reaching for a glass of fatty milk.

Arielle Duhaime-Ross is freelance science journalist, artist, podcast, and TV host based in Portland, OR.

Peter Whoriskey is a Staff Writer at the The Washington Post in Washington, D.C..

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I am Ira Flatow.

What should we eat? The US Department of Agricultural Services updated their recommendations for what makes up a healthy diet. Part of this process is convening a panel of experts to research and write a report, which came out in February.

In September, the British Medical Journal, the BMJ, published what it deemed an investigation into the report, which asked, quote, “Why does the expert advice underpinning US government dietary guidelines not take account of all the relevant scientific evidence?” A group of scientists is pushing back against this BMJ article.

Here with the details of the peak across the pond and other selected short subjects in science is Arielle Duhaime-Ross. She is a science reporter at The Verge in New York. She’s here. Welcome back.

ARIELLE DUHAIME-ROSS: Hi, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s talk about why are scientists criticizing the BMJ investigation.

ARIELLE DUHAIME-ROSS: Right. Well, the first thing you should know about this is that 183 scientists from around the world have signed a letter asking the BMJ to retract the investigation that they published in September, the one that you mentioned. This investigation, like you said, went after the report that informs the dietary guidelines that the US government will put out later this year.

And these guidelines are really important. They’re important because they influence things like school lunches, and nutritional labels, and even scientific studies for the next five years.

But the article that was published in the BMJ suggested that the committee responsible for the report had abandoned a bunch of established methods that could have given better guidelines in the end and also had the article said that the committee head deleted meat from the list of recommended foods.

Now, a lot of scientists and some journalists have pointed out that these issues that the investigation raises, some of them are misleading and some of them are downright incorrect. For example, the deleting meat statement, that isn’t correct.

IRA FLATOW: And I can’t imagine the guidelines taking meat out of everybody’s diet.

ARIELLE DUHAIME-ROSS: Well, right. So actually, the amount that the committee recommends that Americans should eat, the amount of meat, has not changed between the 2010 and 2015 report. And the report actually states quite clearly that lean meats can be a part of a healthy diet.

But the BMJ wrote this. And now, even though 183 scientists, including the chair of the nutrition department of Harvard University has signed on, it’s unclear if this will do anything.

The BMJ has said over the past last month or so that it stands by its story. At the same time, they’ve issued a clarification that just said, we could have been more clear in the way that we were writing the story. And they’ve also issued a correction, but only for one error. So we’ll have to see what happens with this.

IRA FLATOW: I love when these fights happen. Let’s move on to NASA’s MAVEN mission, which seems to have discovered a key clue to something we always wondered about. Where did the Martian atmosphere go?

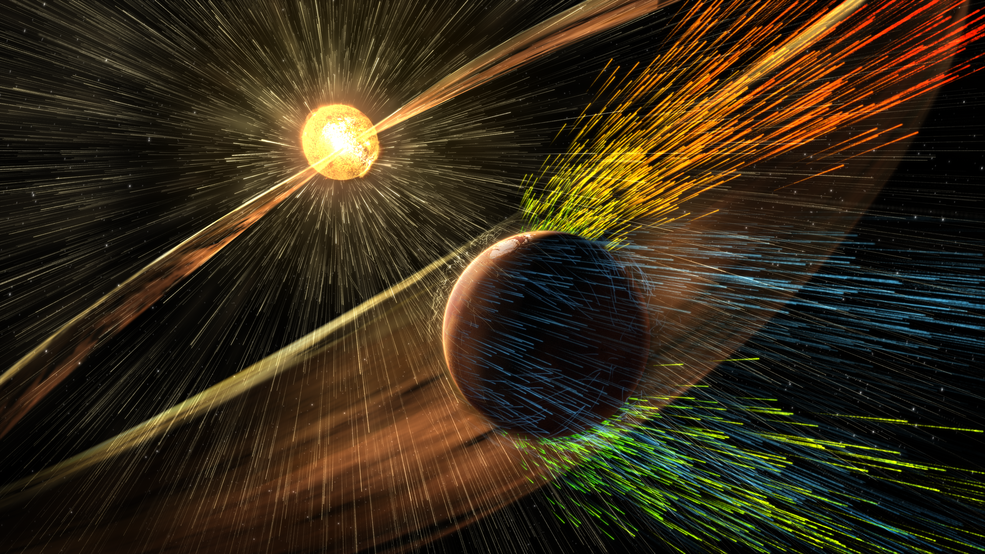

ARIELLE DUHAIME-ROSS: Right. So researchers working on the MAVEN satellite have been gathering data about the Martian atmosphere for the past year. And what they found is that Mars atmosphere is being removed at very high altitudes through its interactions with the sun.

To understand this finding, you first have to know that the sun emits a constant stream of charged particles called the solar wind. And this wind carries magnetic fields. And these magnetic fields hit Mars, which generates electric fields.

And then, this accelerates the ions in the atmosphere, which has one of two results. Either the ions are hurled off into space or they hit other constituents of the atmosphere and then they’re also hurled off into space.

IRA FLATOW: They sweep the atmosphere away.

ARIELLE DUHAIME-ROSS: Right. So essentially the atmosphere is leaking out into space. And right now, the rate of loss is kind of small. But this has been happening for 4.5 billion years. So you know, the accumulation of that is kind of significant.

IRA FLATOW: And that would explain why it lost the water or lost its atmosphere. It went from a wet place– we see now– to the dry.

ARIELLE DUHAIME-ROSS: Right. So that’s why it’s exciting. It explains why Mars has changed so much over the past four billion years. The sun is probably responsible for that change, because as the atmosphere leaked out, then there was nothing to protect the oceans that were covering Mars. And then, those also have gone away. And Mars’s atmosphere is now very, very thin.

IRA FLATOW: So why did that not happen on Earth? Because we’re similar planets, right?

ARIELLE DUHAIME-ROSS: The reason is that Earth has a strong magnetic field that protects it from those solar winds. Mars’s magnetic field is very, very weak. And that planet basically has nothing to protect it.

IRA FLATOW: Because we have this liquid core, that’s floating or sort of slushing around.

ARIELLE DUHAIME-ROSS: Yeah. The iron core.

IRA FLATOW: Iron core. Mars doesn’t have that.

ARIELLE DUHAIME-ROSS: Well, it has frozen over. It used to be like ours, and that used to cause this very, very strong magnetic field. But that froze over billions of years ago. And now, there’s no magnetic field. Or a very weak one.

ARIELLE DUHAIME-ROSS: It sounds like also another story you’re covering, like antibiotic-resistant bacteria gonorrhea has more staying power than people.

ARIELLE DUHAIME-ROSS: Right. So a study published in JAMA this week showed that gonorrhea, this sexually transmitted infection, the bacteria that causes it has increased resistance to an antibiotic that I’m going to pronounce probably wrong. It’s called cefixime.

IRA FLATOW: OK. I’ll take it.

ARIELLE DUHAIME-ROSS: And now, the problem of antibiotic resistance to gonorrhea isn’t new. Between 2006 and 2011, resistance to this antibiotic has increased from 0.1% to 1.4%.

And because of this, the CDC changed the recommended therapy for this drug in 2010 and combined it with another antibiotic. Then in 2012, the CDC actually stopped recommending it altogether, and instead said that you should take another combination therapy.

And for a while, that actually seem to work. The resistance that this bacteria had to that antibiotic I first mentioned, cefixime, went down to 0.4%. But now, it seems that it’s actually gone back up to 0.8%, which it’s unclear why this has happened.

But it shows that even the CDC’s actions probably have not helped change the way that this works. And basically, people are probably still recommending this therapy, even though the CDC says that you shouldn’t. So we’re definitely not out of the woods.

IRA FLATOW: That’s not a good thing to hear. Finally, we always think that diamonds are rare. But they could really be a dime a dozen, so to speak, down in the Earth.

ARIELLE DUHAIME-ROSS: Yeah. Diamonds may be really common very, very deep in the earth. So it’s generally thought that the way that diamonds are formed naturally is through a complex chemical reactions as different kinds of fluids move through rock. But this new study that was put out by a scientist at John Hopkins University suggests a new theoretical alternative model for how diamonds are formed in the earth.

They suggest that at very, very high temperatures, over 1,600 degrees Fahrenheit, and very high pressures, water conform diamonds naturally as it moves from one kind of rock to another. And the key to this chemical reaction is that the water becomes more acidic during this process.

IRA FLATOW: So the diamonds they would be very deep down if we would have to get them.

ARIELLE DUHAIME-ROSS: Right. And not only that, well, they’d be forming at 100 miles below the surface, which is 10 times deeper than any drilling exploration we’ve had. But not only that, they’d also be essentially microscopic, like almost microscopic.

So these diamonds were not going to be something that you’re going to put on a ring. And because they’re so deep, it will take humanity a very, very long time to verify this model.

IRA FLATOW: I’m not going to wait around here for that. Thank you very much. Arielle Duhaime-Ross is a science reporter at The Verge in New York.

Now, it’s time to play good thing, bad thing.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Because every story has a flip side. Now that we’ve been talking a bit about diets, what do you think of whole milk? Are you the kind of person who looks around to see who is watching when you add whole milk to the coffee? Or is it part of a healthy balanced diet that you freely consume in the light of day?

Well, views on the beverage are changing. And here with the whole story on whole milk is Peter Whoriskey. He is a staff writer with the Washington Post in Washington DC. Welcome to the program.

PETER WHORISKEY: Hi.

IRA FLATOW: Now, we normally start with the good of good things, bad things. But let’s talk about what’s long thought to be bad. What’s long thought to be bad about whole milk?

PETER WHORISKEY: Well, our problem with whole milk goes back– well, back to the ’50s– when we start to think that saturated fats were a really bad thing for all of us. And the saturated fats raise the levels of bad cholesterol in our blood. That raises our risks of heart disease. That’s the primary reason that people have gone after it.

But the other problem people– for some people, anyways– is that whole milk has more calories. So a cup of whole milk has 150 calories. A cup of skim has 90 calories.

IRA FLATOW: So we always thought that gave whole milk a bad rap. So are there any benefits? What’s the good thing about drinking whole milk instead of low fat milk, for example?

PETER WHORISKEY: Well, over the years, the government’s case against saturated fats has slowly and steadily crumbled. And there’s been study after study after study saying saturated fats don’t seem to be linked to heart disease in the ways that we thought they were.

And now, there’s newer stuff saying that milk– actually, full fat milk– tends to reduce our risk of heart disease. It tends to reduce our risks of metabolic syndrome, which is that syndrome that’s predictive of heart disease and diabetes. There’s a whole host of new research into the intricacies of cholesterol. And one of the things that, of course, we know now is that whole milk raises the good cholesterol while it also raises the bad.

IRA FLATOW: And when it comes to bad cholesterol, there’s bad and then there’s really bad cholesterol

PETER WHORISKEY: Right. That was one of the findings that’s more recent vintage. And there’s light and fluffy bad cholesterol. And then, there’s small dense particles of bad cholesterol. And the light and fluffy is what saturated fats like that are in whole milk tend to increase. And those are not quite as harmful.

IRA FLATOW: And so the USDA, which we talk about, which comes out with dietary recommendations, they’re not going to be changing their recommendations.

ARIELLE DUHAIME-ROSS: Well, despite the fact that people think they ought to, it looks like they’re going to come down again and say that whole milk is bad and low fat, very low fat, or skim is better. But it’s hard to tell. The book will be out later this year or early next.

IRA FLATOW: All right. We’ll talk more about it later. Thank you, Peter, for taking time to be with us today.

ARIELLE DUHAIME-ROSS: Thank you.

IRA FLATOW: Peter Whorisky is a staff writer with the Washington Post in Washington DC.

We’re going to take a break. And we’re going to be taking a look at what we do and don’t know about the long-term effects of concussions and brain trauma from playing football, hockey, even boxing. We’re going to talk about that with a new guest to talk about it.

Stay with us. We’ll be right back after this break.

Becky Fogel is a newscast host and producer at Texas Standard, a daily news show broadcast by KUT in Austin, Texas. She was formerly Science Friday’s production assistant.