Here There Be Seadragons

Researchers discovered a new type of seadragon, bringing the total number of known species to a whopping three.

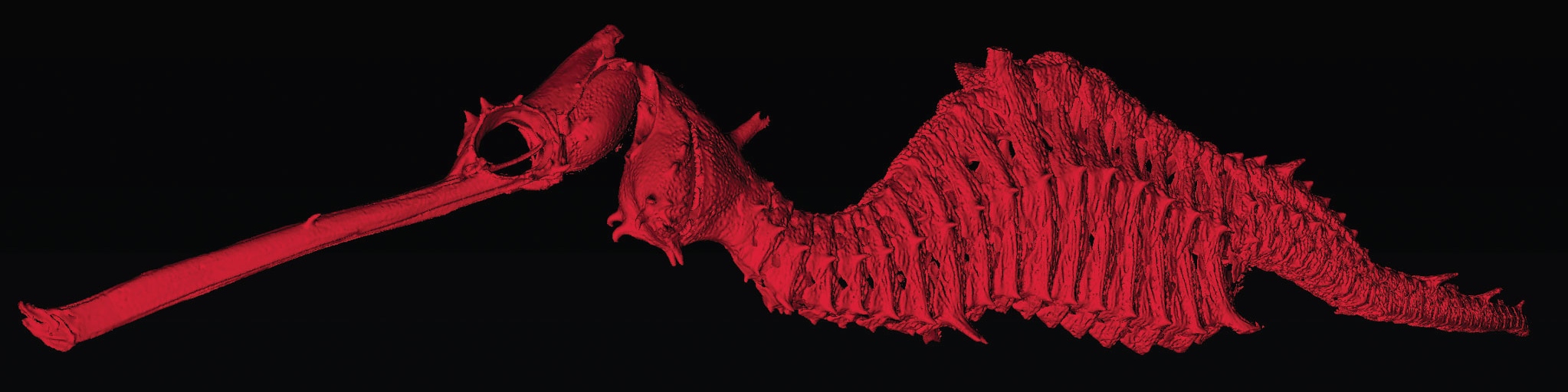

The 3-D skeleton of the ruby seadragon (Phyllopteryx dewysea), constructed from thousands of x-rays obtained with a CT scanner. The color was added to represent the seadragon's hue in the wild. Copyright: Josefin Stiller, Nerida Wilson, and Greg Rouse.

This story has been resurfaced as part of Oceans Month, where we explore the science throughout the world’s oceans and meet the people who study them. Want to dive in with us? Find all of our stories here.

This story has been resurfaced as part of Oceans Month, where we explore the science throughout the world’s oceans and meet the people who study them. Want to dive in with us? Find all of our stories here.

With its vibrant red coloring, the ruby seadragon hardly seems like a stealthy creature. Yet the marine fish evaded discovery until only recently.

It all started with a tissue sample. Josefin Stiller, a graduate student at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, is studying the relatedness of seadragon populations. The delicate fish live exclusively in the waters off the southern coast of Western Australia, and for the past 150 years scientists have assumed that there are only two species: the orange-tinted leafy seadragon and the yellow-speckled common seadragon. For her research, Stiller examined numerous tissue samples from living seadragons (“They don’t swim very fast,” explains Greg Rouse, a professor at Scripps and Stiller’s advisor, who gathered many of the samples). She also asked museums to comb their collections for additional snippets of the ethereal animals.

[Marine habitats are protected—but are they effective?]

One sample, from the tail of a seadragon sent by Perth’s Western Australian Museum, didn’t look like anything special. But DNA sequencing revealed a startling finding: It came from what seemed to be a third, previously unknown species. “It was a huge surprise,” says Stiller.

Stiller then requested the full animal, a male carrying several dozen babies under its tail. Color had drained out of the creature—a byproduct of being preserved in ethanol—but a photo snapped when the seadragon was captured in 2007 revealed that it was originally bright red, hence the name Stiller and her collaborators gave it. She used a CT scan to obtain 5,000 X-ray slices and assembled them into a rotating 3-D model. “It revealed distinct skeletal features,” says Rouse. “It was clearly a different species.”

Meanwhile, Nerida Wilson, a senior research scientist at the Western Australian Museum who worked with Stiller and Rouse, dove into the museum collection to see if she could dig up any more ruby seadragons. “I’m not sure how many jars of wet-preserved animals and drawers of dried specimens we looked through,” she wrote in an email. She hit the jackpot again, this time unearthing one that had washed ashore in Perth in 1919.

[What to expect from an expecting seahorse.]

Stiller also tracked down two more ruby seadragons archived in the Australian National Fish Collection.

The researchers suggest that one reason the fish evaded discovery for so long is because it seems to live deeper than most recreational scuba divers venture, at 30-plus meters.

Rouse and Stiller plan to return to Australia to search for the ruby seadragon, as well as more of its common and leafy cousins, in the wild. Beachcombers might help gather more information about the newly discovered species, too. In early March, just two weeks after the research team published their findings in Royal Society Open Science, a family walking the shore reportedly came across a ruby seadragon, which one member recognized from a news story about the discovery. “I wonder how many more records of the new species will pop up over the next year or so,” Wilson mused.

Whatever the tally, the ruby seadragon’s obscure existence is most certainly a thing of the past.

Alisa Opar is the articles editor at Audubon magazine and the Western correspondent for OnEarth.