Want more paleoart? Listen to Gabriel Ugueto on Science Friday and explore a visual guide of his illustration process. Learn how dinosaurs walked with Science Friday Educate, and see how puppeteers brought dinosaurs to life on stage.

Paleoartist and scientific illustrator Gabriel Ugueto has a golden rule for his work: Accuracy. And he says that’s not to be confused with realism.

Paleoartist and scientific illustrator Gabriel Ugueto has a golden rule for his work: Accuracy. And he says that’s not to be confused with realism.

“Accuracy, based on what we know, is one of the most important things I can showcase in my work,” he says, “and we do what we can with the evidence that we have so far… Realism is very difficult because we don’t know exactly what these animals looked like. It’s just all suggestions and interpretations.”

As a paleoartist, Ugueto reconstructs and illustrates prehistoric animals that aren’t around anymore. You might see his work in books, museums, documentaries, or even scientific journals that deal with extinct animals.

[Why do dinosaurs matter, anyway?]

In order to resurrect the dinosaurs and other ancient creatures, Ugueto begins with a single bone and works his way from inside out. He researches whether there are any related animals alive today, or existing fossils that may shed light on how the bone fragment fits into a larger piece, and reconstructs the entire skeletal system. He then sketches in muscle groups, and adds skin and color considering where the animal lived and during what period of time.

But his resulting illustrations often don’t match the Jurassic Park-inspired dinosaurs that we’re used to.

“I think there’s a big boom in paleoart right now, because there are a lot of recent discoveries and science is allowing us to look at dinosaurs in a whole different way,” Ugueto says. “We know now what coloration they could have had. We know a lot more about the way they were related to each other. We know now more than ever about how they could have behaved, who they are related to… There is a huge renaissance to make these animals more accurate.”

Enjoy Ugueto’s reinterpretations of some of the prehistoric animals that we thought we knew so well:

Plesiosaurs

Until recently, Ugueto explains, people thought that plesiosaurs had smooth, taut skin. Then, researchers unearthed a “beautifully preserved” plesiosaur in Mexico.

The finding revealed two new discoveries: Skin impressions revealing tiny scales, and blubber-like deposits around the body, particularly around the tail and neck.

“I think, for a long time, paleoart suffered from skin-wrapping everything,” Ugueto says. “We didn’t give any room for fat deposits, muscles, and everything looked really like the animals were anorexic… but we have to keep in mind that they were alive.”

[Looking for some micrometeorites? Check the roof.]

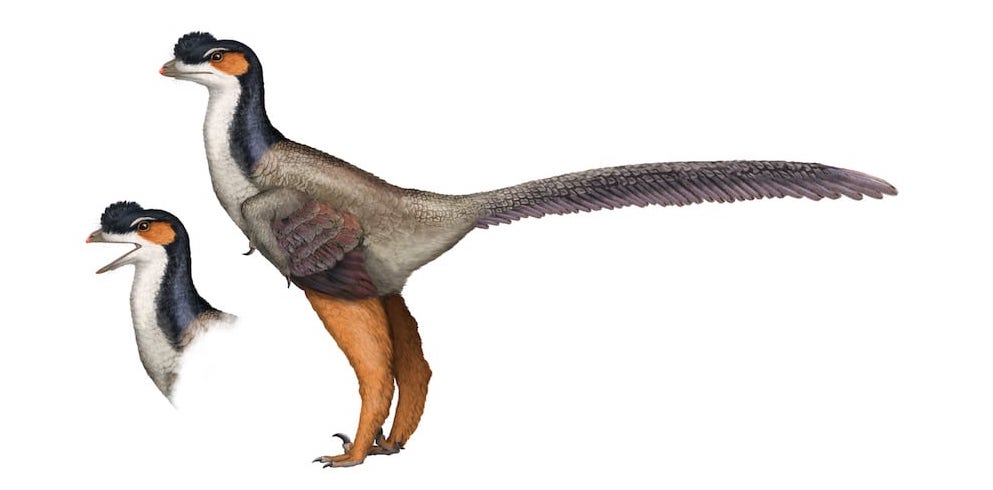

Theropods

We may now know that birds are modern dinosaurs, but the feathers they sport go way back—and they didn’t always appear only on the dinos that flew.

“We have evidence for many, many groups of non-avian dinosaurs that they had feathers,” says Ugueto. And these dinosaurs had plenty of different types of feathers, he explains, from very simple ones that look more like hair to the types of feathers that can be still found on birds like pigeons today.

“But we don’t know exactly where the origin of feathers started,” he explains. “And some people even think that pycnofibers are present on pterosaurs, which are those little hair-like structures, are probably homologous with feathers. So if that is the case, then the ancestor of both pterosaurs and dinosaurs had feathers or some sort of feather-like integument.”

Tyrannosaurus rex

Perhaps the most commonly-depicted dinosaur, Tyrannosaurus rex is usually shown as a terrifying, glamorous, photogenic lizard. But in reality, the mighty T. rex was a bit scruffier around the edges than you’ve been lead to believe.

“What I learned is that you have to be really careful how you reconstruct teeth,” says Ugueto. Like humans, dinosaurs periodically lost some teeth. But unlike humans, they grew new ones. Those perfectly aligned and filled sets of chompers that we may see in movies aren’t very accurate—Ugueto takes care to reconstruct dinosaurs with teeth in various stages of development.

And if this T. rex looks a bit grizzled, that’s because it likely was. “It is known that tyrannosaurs had a very violent social life,” says Ugueto. “They bit each other’s face frequently, and they have a lot of scars in the fossils.” When illustrating their heads, Ugueto takes care to depict the scarring from all those scuffles.

And finally, while tyrannosaurs were mostly scaly, that doesn’t meant that they didn’t have feathers on parts of their bodies, says Ugueto.

[From bones to blades, the history of ice skates.]

Deinocheirus

When he’s not doing strictly paleontological work, Ugueto occasionally gets to flex his artistic muscles a little more, as in this illustration of an irritable deinocheirus, above.

In order to flesh out the pond scene, Ugueto infused some character into his resurrection, and imagined the deinocheirus defending its territory

“If you’ve ever been around swans or geese or ducks, you know they’re super cranky,” says Ugueto. “And a lot of times too, I think dinosaurs were probably cranky also, only with a lot more teeth and a lot more attitude and a bigger size.” In fact, the deinocheirus depicted above was about the size of a T. rex.

The deinocheirus was likely omnivorous or herbivorous, so Ugueto wanted to resurrect the deinocheirus as a creature that wasn’t predatory, but was “aggressive in the sense of defending its territory.”

Anurognathus

Sometimes, Ugueto’s recreations seem almost too astonishing to be true. When he brought this illustration of the Anurognathus to the printer, he had an exchange with the woman behind the counter, who couldn’t believe that such an animal had once roamed the earth. Ugueto compares this pterosaur called Anurognathus, depicted above, to a porg from The Last Jedi.

Ugueto says it’s easy for people to be surprised and amazed when they see his recreations. But the feeling goes both ways: “I think part of it is the rush of creating something that looks so bizarre, and it fuels your imagination to think, ‘What were they doing? How could they have behaved? What were those weird structures they had for?’” he muses.

Even for a paleoartist, the creatures can be surprising and amazing.

Correction 3/16/18: A previous version of this article implied that plesiosaurs and pterosaurs are dinosaurs. Plesiosaurs are marine reptiles, not dinosaurs, and pterosaurs, while closely related, are not dinosaurs either. We’ve clarified the language and regret the error.

Credits

Produced by Luke Groskin

Music by Audio Network

Illustrations by Gabriel Ugueto

Article by Johanna Mayer

Additional Images by Shutterstock and E. Frey

Meet the Producer

About Luke Groskin

@lgroskinLuke Groskin is Science Friday’s video producer. He’s on a mission to make you love spiders and other odd creatures.