Progress on a Universal Cancer Vaccine, an Inflatable Space Habitat, and Blocking Mobile Ads

11:50 minutes

A team of German scientists announced a “very positive” step in recruiting the immune system to help the body fight cancer. Their research looked at using cancer RNA nanoparticles injected into a patient’s bloodstream, which triggered an immune response that attacked tumors. Sophie Bushwick, a senior editor at Popular Science, explains why this strategy could someday lead researchers to a universal vaccine that could be customized to fight nearly any kind of cancer.

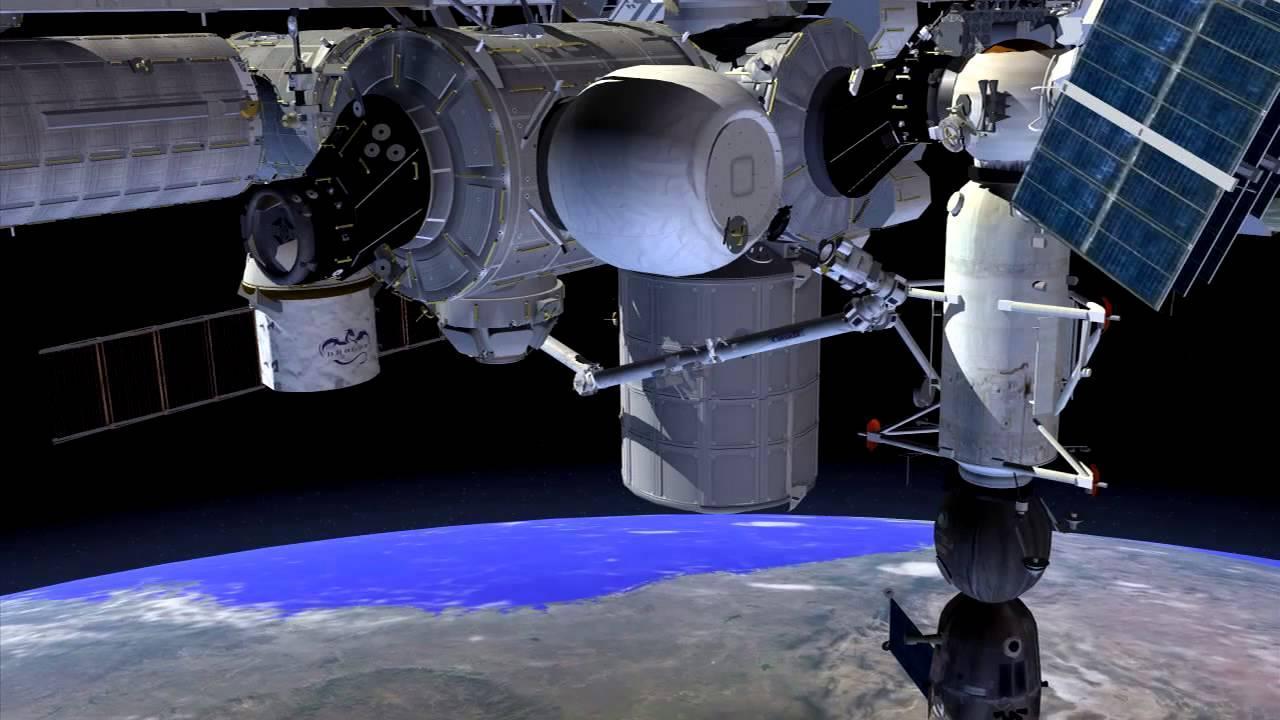

Plus, Bushwick shares the saga of the BEAM inflatable space habitat, now in commission aboard the International Space Station, and Slate technology writer Will Oremus walks us through the good and bad of mobile ad-blocking software.

Sophie Bushwick is senior news editor at New Scientist in New York, New York. Previously, she was a senior editor at Popular Science and technology editor at Scientific American.

Will Oremus is a senior technology writer for Slate in New York, New York.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. A little bit later in the hour we’re going to look at a few old therapies that researchers are resurrecting as we run out of antibiotics to treat super bugs.

But first, researchers have been trying to find ways to harness the power of the body’s own immune system to fight cancer. And now, one group of researchers may have made a step, an important step, toward a universal vaccine that would teach the body to fight any kind of cancer with the same tools that the body uses to fight viruses. Here to explain that development, plus other short subjects in science, is Sophie Bushwick, senior editor at Popular Science. Welcome to Science Friday.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: I’m happy to be here.

IRA FLATOW: Nice to have you. Walk us through the actual research findings. What was discovered?

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: So the researchers– researchers for awhile have been trying to find ways to get the immune system to attack cancer, but the problem is that cancer cells are just too similar to the normal cells of the human body. So what these researchers did is they created nanoparticles from RNA. It’s basically RNA enclosed in a little envelope made of fatty acids. And then they gave these nanoparticles a slight negative charge so they could steer them, and then they put them into the spleen and other lymphoid tissue in the body where these nanoparticles targeted dendritic cells.

Dendritic cells are kind of like the messengers of the immune system, and so they got these envelopes of RNA and they thought that they were viruses. And so they primed the immune system to respond, as if to a virus, and to attack these tumors. So they so far have only tested it in models of mouse tumors and in three human patients with advanced melanoma, but they’re saying that this technique really could be applied to a lot of other kinds of cancer.

IRA FLATOW: So in phase one, it sounds like for the patients.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: That’s right.

IRA FLATOW: That it was not toxic is what they’re testing for. Any hint that it might have actually helped or worked in those patients?

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: They did find it did prime the immune system–

IRA FLATOW: It did?

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: –yeah, to respond to the tumors.

IRA FLATOW: This is exciting. Using nanoparticles–

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: Yeah, that’s right.

IRA FLATOW: –to create– writing it on a virus?

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: Right. The nanoparticles– the body thinks that these particles are viruses. They say, oh, here is this RNA. It’s surrounded by some fatty acid. This is clearly a virus. We should attack it. And so it gets the immune system up and fighting.

IRA FLATOW: Well, that is interesting.

Let’s talk about astronauts on the International Space Station, and they are testing a potential habitat for camping out on other planets. This inflatable little pod or something. We talked about this before. It was having trouble being inflated.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: Yeah. Last week they wanted to inflate it on Thursday. It’s the Bigelow Expendable Activity Module, but BEAM for short.

IRA FLATOW: Of course.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: And apparently they think it might have been in storage for a little too long, which made the material kind of stiff. But over the weekend they did successfully inflate it. It’s sort of this pod shaped object. And when it’s not inflated it’s about seven feet long. And when they do inflate it, it almost doubles in length to 13 feet long, which gives you about 565 cubic feet of space to play around in. So they did inflate it, and now they’re testing it for leaks. And the next step is going to be to have an astronaut actually go into the module and check it out, and then it’s going to be on the space station for two years.

IRA FLATOW: Two years?

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: Two years, yeah. They need to test it and make sure it can stand up to debris and to the crazy temperatures in space and all that.

IRA FLATOW: It must be strong material.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: It is. It’s actually a fabric, but it’s a proprietary material that’s–

IRA FLATOW: It’s not just plain Kevlar, or something like that?

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: It’s not Kevlar. You could compare it to that. It’s kind of a similarly very sturdy material, and it’s lots of layers of this fabric with air in between.

IRA FLATOW: If this proves to work, isn’t this the kind of stuff you could build a habitat on Mars? Maybe Elon Musk wants some of this stuff to take with him to Mars.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: Absolutely. You could put these habitats on the moon or on Mars for humans to live in because they’re very light. So for every cubic foot of space in BEAM you’ve got about five pounds of weight. And compare that to the ISS where for every cubic foot of space it’s about 30 pounds of weight. So this is so much lighter that it’s a much more practical way– it’s a much more practical habitat for people to take into space.

IRA FLATOW: I’ve got to tell you. You’re not old enough to remember how radical an idea this is for NASA to build something that’s inflatable. [LAUGHTER]

Let’s move on to your next topic, which is– we learned this week that the opioid painkillers may not be good for painkilling in the long term.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: This is a kind of disturbing study. They looked at rats that were in pain, and they treated some of them with morphine for five days and the other ones they didn’t treat with drugs. And what they found was the ones that were treated took about 10 to 11 weeks to stop feeling pain from their injury, whereas the rats that weren’t treated recovered in half the time, only five weeks.

So what the researchers think was going on was that the immune system of the rats that were treated with morphine, their immune systems were attacking these opioids in the body, and that caused irritation that prolonged pain in the rats that were treated with morphine. But the good news is the researchers are saying that possibly you could prevent this effect from happening by suppressing that immune response.

IRA FLATOW: What kind of pain was it? Where did it come from?

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: They pinched the sciatic nerve in the leg.

IRA FLATOW: Ooh!

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: Yeah.

IRA FLATOW: I know when that acts up what that feels like.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: And then in order to test how long the mice were in pain, they pinched their paws. And if they’re still in pain from the sciatic nerve or from reaction to these opioids, then the mice were– the rats, I’m sorry– were more likely to flinch.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. So I guess we’ll be watching this because it has implications for humans.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: Absolutely. I mean, we’re pretty much in what the FDA is calling an epidemic of substance abuse of opioids, whether it’s heroin or prescription drugs, prescription painkillers like Vicodin. There’s a lot of addiction and a lot of issues with that.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. And finally, my favorite story of them all is the famous Dr. Henry Heimlich finally performed the Heimlich maneuver at the age of 96.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: That’s right, he says he’s–

IRA FLATOW: He never did this before in his life?

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: He says he’s never done it before. He says he’s demonstrated it, but never used it on someone who was choking. But he is 96. He’s retired. He’s living in a retirement home, and he says that he was at dinner and a woman began choking. And so he turned to her and performed the Heimlich maneuver, and the food flew out of her mouth and she was saved. And it’s pretty amazing that at the age of 96 he’s finally getting to try his technique for the first time.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. It’s good that it all worked, and everything turned out OK.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: Yeah.

IRA FLATOW: All right. Thank you. Thank you, Sophie.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: Thanks.

IRA FLATOW: Interesting stuff. Sophie Bushwick, senior editor at Popular Science. And now it’s time to play good thing, bad thing.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Because every story has a flip side, it won’t come as a surprise to anyone when I say that the online world is full of ads, hovering, covering, blinking, sinking. You’ve got dancing ads, every kind and shape. And people are editing out these ads out of their online experience, using something called ad blocking software. New numbers out from two companies, that’s PageFair and Priority Data, say that one in five smartphone users block ads on their mobile devices.

Joining me now to talk about the good and the bad is Will Oremus. He’s senior technology writer at Slate. He’s with me in our New York studios. Welcome back, Will.

WILL OREMUS: Thanks for having me.

IRA FLATOW: All right, are there that many people really blocking ads when they go online?

WILL OREMUS: Well, the specific numbers have been disputed a little bit. So the company that put out this study is actually in the business of selling solutions to media companies–

IRA FLATOW: Why am I not surprised?

WILL OREMUS: –how to stop losing money on ad blocking. That said, the numbers that they had out there do line up pretty well with what I’ve seen anecdotally. A lot of people are blocking ads. Originally, people were doing it on their desktop computers. The news is that now they’re doing it increasingly on their mobile phones.

But that one in five figure, that figure where one in five people are now blocking ads on their smart phones, that could be a little misleading depending on where you are. If you’re in the United States, the figure is actually much, much lower. It’s down around– I believe it’s around 2% of US smartphone users are blocking ads. If you’re in India or Indonesia, or Germany actually, the number is significantly higher than one in five. It’s more like two in five in Germany, and actually the majority in India and Indonesia.

IRA FLATOW: OK. So what’s the good thing? Why are people so happy?

WILL OREMUS: Can we flip this, Ira? Can we start with the bad thing?

IRA FLATOW: You can take over. Go ahead.

WILL OREMUS: Thank you.

IRA FLATOW: The bad thing.

WILL OREMUS: Thank you. This autonomy feels good. The bad thing is, it’s pretty obvious I think, it’s that if everybody did this, I would be personally out of a job. No, the bad thing–

IRA FLATOW: Because that you need the ads?

WILL OREMUS: Yeah. I mean, Slate is an ad supported website. Most media is ad supported. Some media companies have subscribers as well, but even they rely on advertising. You’re safe, I think, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: I’m safe? Why am I safe?

WILL OREMUS: Well, you’re not an ad supported media business.

IRA FLATOW: Well, we do have ads on our website. We do take ads.

WILL OREMUS: Maybe you’re not so safe after all.

IRA FLATOW: We’re not so– we may be not as guilty as, though. We don’t have all those ads. We can’t afford to place them.

WILL OREMUS: Well, good for you. But the issue is that this model that the media have relied on for a long time could really break if this number increases dramatically. If so many people are blocking these ads, then the websites have no way to get money out of their visits and a lot of them will go out of business. And all that information that we want to be free, will no longer be free.

IRA FLATOW: Now I would think that the good side– and now I’m going to reverse, and I’m going to tell you what I think the good side is.

WILL OREMUS: Fair play.

IRA FLATOW: You know you’re going to get ads, right? And they know how to curate them, only show you the ads that you want to see. Would that be considered a good thing instead of getting all the kinds of ads?

WILL OREMUS: Yeah, so the good thing here– I mean, there’s one really obvious and practical good thing, which is that the people who are using this software are having a really nice, smooth experience on their phones without all these junky ads that you talked about. The other good thing, which you just alluded to, is a little more theoretical, and it’s this idea that basically websites have been bombarding people with these terrible ads because they can get away with it. You don’t have a choice. You go to a website and you get assaulted with these horrible ads.

Now that people do have a choice, theoretically, it could incentivize media companies and advertisers to clean up their act, and to start presenting ads that people actually want to see. I mean, if you think about the old model of the newspaper, there were ads in there– you wanted to see the auto ads or the classifieds. There was stuff in there that you actually bought the paper partly to see. If you can make ads better in response to this, then I think that would certainly be a good thing. But there’s a question of, how do we get there from where we are today?

IRA FLATOW: Is there something in model, maybe– I know in the gaming app world there’s a model freemium. There’s an ad– the app is free, but you pay for all kinds of add-ons in the game, as you play the game. Hey, I want to go to another level. You pay for that.

WILL OREMUS: Yes. So a freemium model is one possibility where maybe you get an ad free version of a site if you’re willing to pay for it. I don’t personally put a lot of stock in that as the solution. Because if you can block the ads for free, then why would you pay to block the ads?

IRA FLATOW: OK. You know, I don’t have an answer. You’ll have to come back.

Well, thank you, Will. You left us thinking about something this afternoon. Will Oremus is senior technology writer at Slate. Thanks for coming back again.

WILL OREMUS: Thanks, Ira.

Copyright © 2016 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of ScienceFriday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies.

Christie Taylor was a producer for Science Friday. Her days involved diligent research, too many phone calls for an introvert, and asking scientists if they have any audio of that narwhal heartbeat.

As Science Friday’s director and senior producer, Charles Bergquist channels the chaos of a live production studio into something sounding like a radio program. Favorite topics include planetary sciences, chemistry, materials, and shiny things with blinking lights.