Are ALL Minnesotans Above Average?

12:22 minutes

This week, Science Friday took the stage at one of public radio’s most revered venues: The Fitzgerald Theater, in St. Paul, Minnesota, home to Garrison Keillor’s “A Prairie Home Companion.” From the Fitz’s stage, Keillor regularly shares the news from Lake Wobegon, the fictional Minnesota town where “all the women are strong, all the men are good-looking, and all the children are above average.”

But it’s not just in Lake Wobegon where people believe they’re a step above the average Joe. In fact, social psychologist Jessica Salvatore says the scientific phenomenon known as the “Lake Wobegon Effect” is universal—and she gave our live audience a survey to prove it. Salvatore joined Ira Flatow onstage at the Fitz to analyze more than 400 survey responses from our audience members and reveal whether Minnesotans really do believe they’re above average.

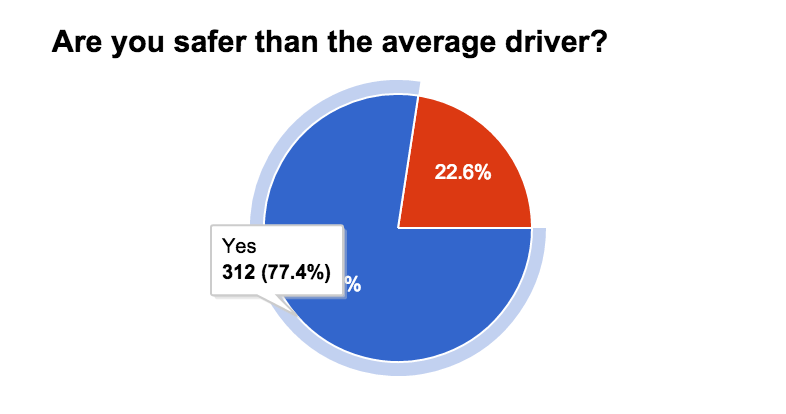

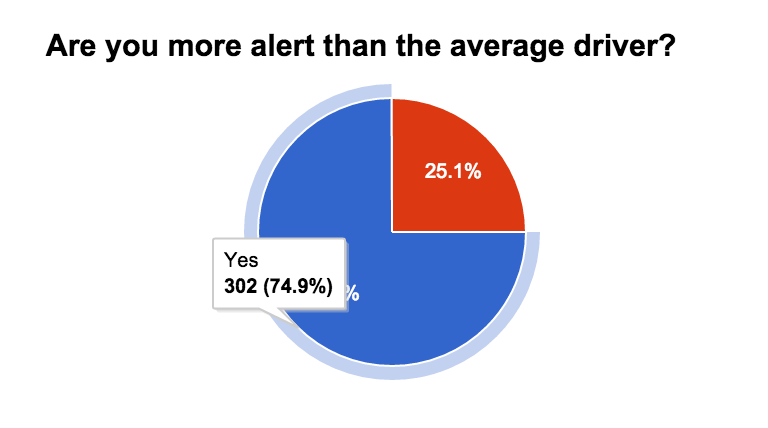

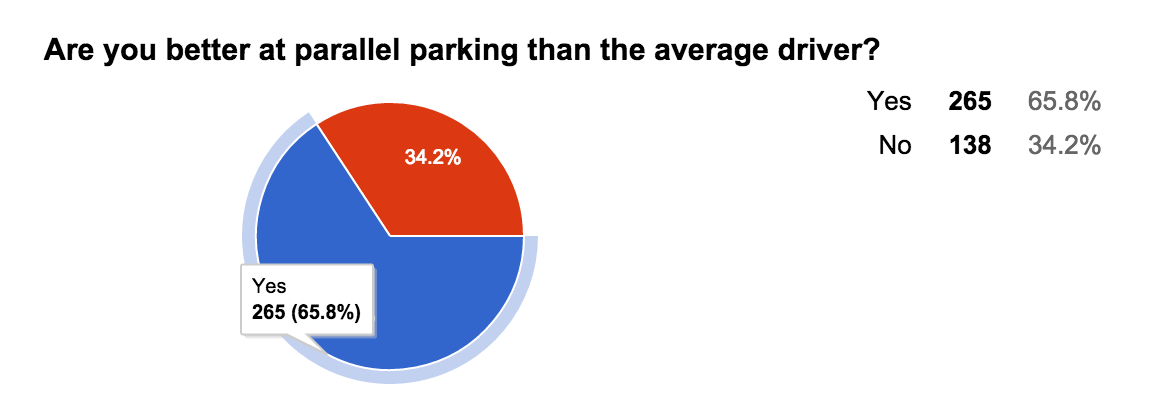

We asked more than 400 members of our Fitzgerald Theater audience to evaluate their driving abilities. See the results below:

Jessica Salvatore is a visiting professor of psychology at Macalester College in St. Paul, Minnesota, and an assistant professor of psychology at Sweet Briar College in Sweet Briar, Virginia.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow coming to you from the Fitzgerald Theater in downtown Saint Paul. Now here at the Fitz we are really treading on Public Radio sacred ground. This theater is home to one of your favorite radio shows. It’s home to the Chatterbox Cafe. We have the gloom-filled office of Guy Noir. And in the green room, you’ll find a heaping plate of powder milk biscuits.

If you need another hint, how about this. That’s the news from Lake Wobegon, where all the women are strong, all the men are good-looking, and all the children are above average. Yeah. That’s right. Tonight we’re in the home theater of Prairie Home Companion, where each week Garrison Keillor gives us the news from the little town that time forgot.

But if you’re a science geek like me, there’s something that bothers you about all of Lake Wobegon. I mean, how could all the children be above average? You ever wonder about that? Yeah?

Well, you know what, it’s not just Lake Wobegon where they feel that way, where they believe that their kids are a step above average. In fact, the scientific phenomenon is known as the Lake Wobegon effect. And it’s universal. And it’s alive and well right here in Saint Paul.

Jessica Salvatore is a visiting professor at Macalester. And she’s an assistant professor of psychology at Sweet Briar College in Sweet Briar, Virginia. And tonight she will rally the power of data, your data, to tell us if we are as super and above average as we think. Welcome. Welcome to Science Friday.

JESSICA SALVATORE: Thanks, Ira.

[APPLAUSE]

IRA FLATOW: I know that besides being a psychologist, you’re also a Prairie Home Companion groupie, right?

JESSICA SALVATORE: Yeah. That’s a fair statement. It’s part of my family culture to listen to it. We literally listen to it religiously in the sense that we listen to it on the way home from Mass on Saturday night.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. So what is the Lake Wobegon effect? And is it real? What is it?

JESSICA SALVATORE: Yeah. So it’s a bias and inaccuracy of social comparison where we think about the self, we think about other people, and we think wrongly about the relationship between the two. So for example, if I asked all of you and thought about for myself, am I more kind than the average person?

Well, that’s a fuzzy concept right? Kindness. Right. Like, what’s kind?

I have a lot of students. I mean, sometimes I give them an extension. Right? But then sometimes I walk by people in the street who are asking for money.

So I’m just going to think about that first one, because I feel better about thinking about that first one. And then I won’t look for much more evidence about the rest of you. And then I’ll go, yes. I am definitely kinder than average. So that would be an example of it.

IRA FLATOW: And you can trace this idea called– the term the Lake Wobegon effect back to one man.

JESSICA SALVATORE: Yeah. The man is David Myers. And he is a just really critical author of textbooks of both intro and social psychology. In fact, I use his textbook when I took AP psychology in 1997, ’98. And he coined this term. It is also known by other terms. But I think this is the most evocative.

IRA FLATOW: In fact, he’s still around. And we were very curious to find out about the first use of this. So we spoke with him about his Eureka moment when he first made the connection between the above average effect and Lake Wobegon.

DAVID MYERS [RECORDING]: I’m reading and reporting on study after study that shows that most people think they’re better than average on just about any dimension that’s both subjective and socially desirable. And then I hear the introduction to Prairie Home Companion where all the children are above average. And I think, that’s it. Prairie Home Companion captured the world.

IRA FLATOW: And so he was thinking and researching this idea, heard the show, instant term.

JESSICA SALVATORE: A classic.

IRA FLATOW: A classic. Where would that show up in other kinds of actions that we take?

JESSICA SALVATORE: It’s pretty common, to tell you the truth. Right.

IRA FLATOW: I’m looking at the audience. They’re all shaking their heads.

JESSICA SALVATORE: We think of ourselves as more ethical, more competent, more attractive. For example, if I took a photo of each one of you and I morphed it into photos of more attractive people and less attractive people, and then I said, which one is actually the photo of you? It turns out most people would pick one that’s just slightly above their actual photo in attractiveness. And I can really see that with myself.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. And is it true that even violent criminals think that they’re kinder and more trustworthy?

JESSICA SALVATORE: Yes.

IRA FLATOW: Than most people.

JESSICA SALVATORE: It is. Isn’t that shocking? So if we find populations of people who we think have already proved themselves through their actions to be on the low end of this dimension, they nonetheless still think of themselves as above average. It’s astounding. It’s so robust in effect.

IRA FLATOW: And we all think of ourselves according to this factor– we think that we are less biased than other people. The other person has to be the one that’s the biased one, right?

JESSICA SALVATORE: Yeah. I call this meta bias. It’s a bias about bias. Right?

In the United States, being independent from social influence is such a strong cultural value, that we all think of ourselves as more independent, less biased, than other people.

IRA FLATOW: And in this political season this must be really playing out. Oh, I’m less biased than you are about this sort of thing. And just in case you our Saint Paul audience thinks– maybe you think you’re immune to this. That’s why we gave you a little quiz at the beginning, at the top of the show.

We asked you to rate your driving compared to other drivers. Jessica, explain what the quiz was really about. What was going?

JESSICA SALVATORE: Yeah. So somewhat similarly to what we just talked about men who had committed violent crimes. There was a study 30, 40 years ago of someone who compared people who had found themselves in the hospital after accidents– driving accidents, some of which they had themselves caused– versus people who had no accident history.

And it turned out that both groups thought of themselves as above average drivers. So that sparks one of the most interesting and easy to remember and notable demonstrations of the better than average effect. And we decided to try to replicate it.

So I have here your data. I love the big reveal. It’s just like class.

So you all voted on the cellphone before.

JESSICA SALVATORE: So 400 of you responded to our question.

IRA FLATOW: 400?

JESSICA SALVATORE: Yeah.

IRA FLATOW: 400? You can’t get 400 people– Wow.

JESSICA SALVATORE: I know. I’m jealous.

IRA FLATOW: Congratulations. Give some applause for yourself.

[APPLAUSE]

JESSICA SALVATORE: It’s exceedingly rare for me to have sample sizes that large. So that’s fantastic. I feel very comfortable with that sample size.

And it turns out that we asked you all, are you a safer driver than the average driver? And 77% of you said yes. So assuming driving ability is normally distributed, then that simply cannot be true. Right?

And also, whether you’re more alert than the average driver. 75%. Not any better.

IRA FLATOW: It’s like Wobegon. You’re above average, right.

JESSICA SALVATORE: No. It might be true for some of you, right? So for 50% of you, that should, in fact, not be incorrect.

So last week when I was talking about this with one of my colleagues, he looked me dead in the eyes, no hint of a smile. I am above average, right? And he could well be completely correct.

So that’s why this illusion of superiority is only an illusion. It’s only a bias at the population level. It’s only because the number overall is over 50% that we know that there’s a bias at work.

IRA FLATOW: So what do we think average means? Why do we all think we have to be above average? What do we think average means?

JESSICA SALVATORE: I mean, average is kind of a dirty word. Average is like mediocrity. So I think we get that in our socialization.

There are a couple of things going on in the above average effect– the Lake Wobegon effect. And one of them is absolutely the idea of motivated reasoning, that we would like to see ourselves in positive terms of slight rose-colored tint to the glasses we have on.

So for example, we do this more so with traits or dimensions that we are invested in. So faculty say that they’re above average teachers more so than people who have no interest in teaching per se. There’s a lot of motivated reasoning and the desire to self-enhance going on here, and in a host of related biases, self-serving bias for example.

IRA FLATOW: Now we’ve all learned this. 77% of the audience thinks they’re above average. The Lake Wobegon effect is working very well in this audience here.

But let’s say that some people in the audience say I want to reform myself. Can I change? Anything I can do about that?

JESSICA SALVATORE: Can you do de-bias yourself? So people who have tried to de-bias participants in lab studies have found that that is temporarily possible. So by educating people, by showing them what the distribution of what other people do is, you can get people to recognize that overall, they’re not going to be all above average, right?

But it turns out it’s a very, very temporary effect. So six weeks later, you bring them back in. And you show them what they said they were like before. And now they go, I’m better than that person. It’s themselves.

IRA FLATOW: You also asked our audience– this is a good question, because I took the test also. Are you better at parallel parking than the average driver? Why did you ask that question?

JESSICA SALVATORE: Our hope was that we could identify a question that has to do with driving skills that would be hard enough that we would see that the bias eliminates itself. And so there’s definitely some data showing that in certain domains systematically, you can see a below average effect. So things that are very, very hard in absolute terms like juggling– like I can’t juggle at all. Right. Or dealing with irritating people, being patient with irritating people, right?

Things that are just really hard. They take a lot of skill, or they just take a lot of saintliness that people sometimes will systematically rate themselves as below average. And our hope was that by asking you about parallel parking, that we would be able to see an elimination, if not a reversal, of the above average effect.

But I am sort of disappointed to say that you all still think of yourself as above average in parallel parking. There is a slight attenuation of the effect. So instead of 75% or 77%, you’re down to only 66%.

IRA FLATOW: There you go! Progress! There you go.

One last question, because in Lake Wobegon, it’s the children who are above average. Do we see that effect when parents talk about their kids?

JESSICA SALVATORE: We absolutely do. Yeah. And what’s really interesting is parents do show this with regard to talking about their children. But what’s interesting is it’s correlated with their own individual ratings of above averageness. So parents who see themselves as, you know, special snowflakes, also see their children as particularly special snowflakes.

I think it’s really helpful to be superheroes in our own minds. But those people are annoying. Right? They’re taking it too far.

IRA FLATOW: Can’t add to that. Thank you very much, Jessica. Now you all know.

Jessica Salvatore is an assistant professor of psychology at Sweet Briar College in Sweet Briar, and a visiting professor at Macalester here in Saint Paul.

Coming up, wearables that make superhuman spider sense a reality. But first, Minnesota’s very own brass messengers.

[APPLAUSE]

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Annie Minoff is a producer for The Journal from Gimlet Media and the Wall Street Journal, and a former co-host and producer of Undiscovered. She also plays the banjo.